A Mundane Textile: History Through a Lost Craft Tradition

Words by Arjunvir Singh & Rashi Sharma

Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labour of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com. Check out our Shop and our Podcast. You can also follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

A Mundane Textile: History Through a Lost Craft Tradition by Arjunvir Singh & Rashi Sharma

“Suzani of Kashmir,” Rashi and I pointed out to each other as the obvious subject for our classroom research project. It was 2018, and July, and Ahmedabad was simmering in heat as usual. On day one of our fifth semester, as students of textile design at the National Institute of Design, we were required to start preparing a proposal for a project scheduled for later that semester. We knew that it was going to be our first research-heavy project, wherein we were not expected to develop tactile surfaces, but rather document the ones that already existed in the undulating landscape of Indian textile traditions. We decided that we’ll spend our three weeks of fieldwork in Kashmir, exploring an area new to us, locating Suzani embroiderers, and documenting the intricate craft of Kashmiri Suzani, an embroidery tradition based on one of the most intricate chain stitches we had ever come across.

But, much to our disappointment, that proposal was not accepted by our anchor faculty. As it was, we happened to miss out on one important prerequisite, the textile craft had to be from one of our native states which was supposed to make the research more effective owing to familiarity with the region and the local language. Back to square one, we decided to pick up a craft from Punjab, as I had spent all my life in Jalandhar, and Rashi was a Punjabi from Mumbai. So there we had it; Phulkari, Dhurries, Punjabi juttis, Nadas, and Khes, and we had to pick one. We went ahead with Khes because it happened to be the only Punjabi textile that wasn’t written about as much as the others. Our enthusiasm was down a notch because we had to let go of field research in an unfamiliar land, about a textile as beautiful as the place itself, for a mundane daily-use textile craft from our homeland, so regular an object that we thought twice before considering it a ‘craft’. Little did we know that that particular textile was going to be the most important part of our final year at college, and the beginning of our professional careers.

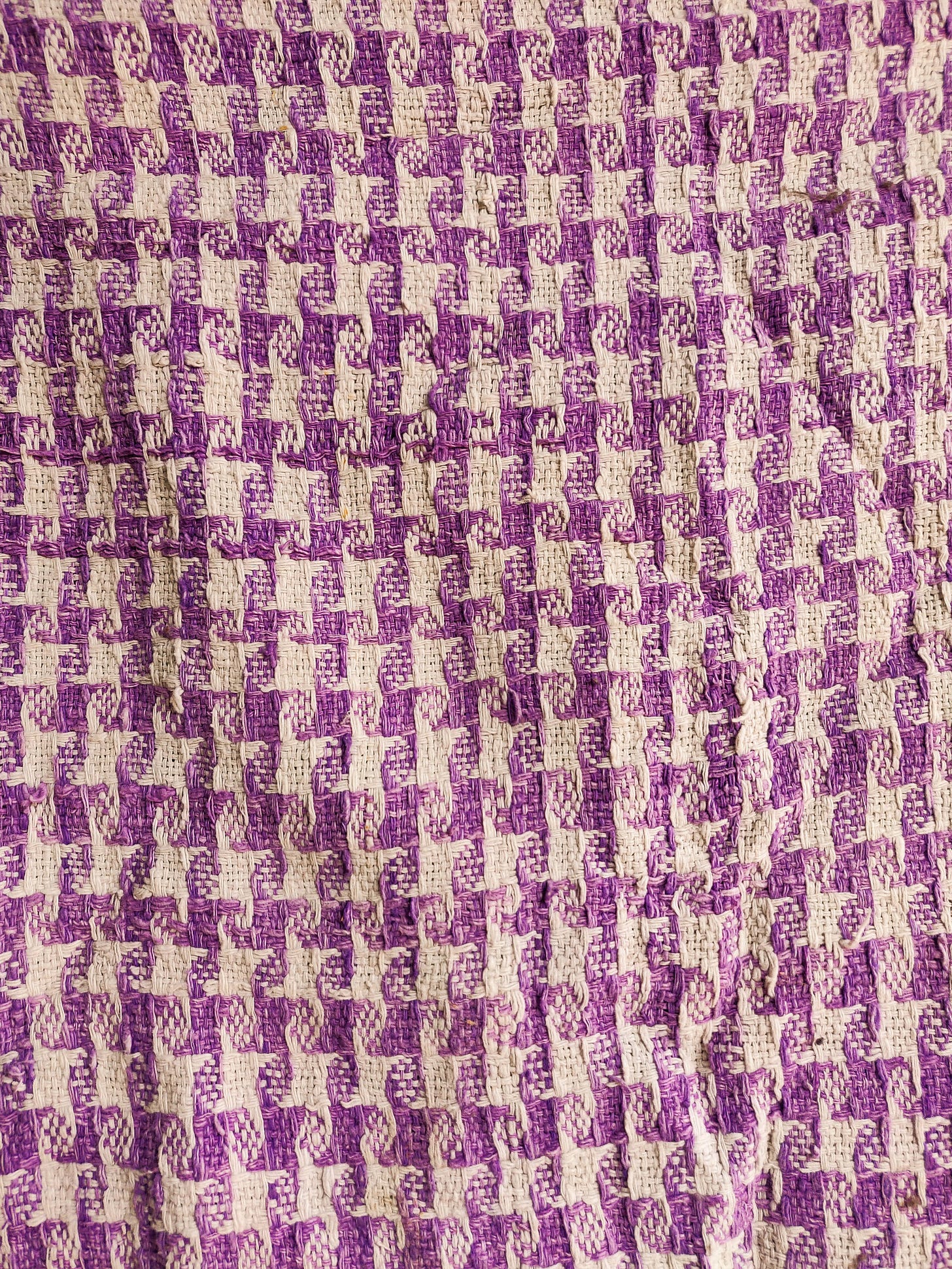

Khes is a cotton bedspread from Punjab, which had multiple purposes in a traditional Punjabi household. Apart from being used as a bedcover, it was used as a shawl, and as a blanket in light winters and summers. It’s a thick cotton fabric made with yarns of a count lighter than those used in a dhurrie but coarser than those used in weaving Khaddar. Khes also used to be an important element of dowry for a bride’s trousseau. When we first started researching Khes, all we knew about it, as a textile object, was that it’s a cotton fabric patterned with simple stripes, checks, and plaids, structured with a twill weave. But as we went ahead, we realised that it was just one type of Khes that we were familiar with. We came across a term — ‘Majnu’ Khes— which was supposed to be patterned with double cloth, a compound weave structure. As students of weaving, it was quite fascinating to us because we had never come across a complicated weave structure being used in Punjab. Moreover, we could not imagine it being done on the pit looms, without any external jacquard machines. For the first time, after having started the project, we came across something interesting, something we hadn’t heard of, and something that we wanted to decode. So we made it a point to locate this particular type of Khes in various parts of Punjab and Haryana during our three weeks of fieldwork.

We went from Jalandhar to Nakodar to Amritsar to Chandigarh to Malerkotla to Patiala to Ludhiana and then to Panipat, but we didn’t find anything about Majnu Khes. No one knew about it. Not even the weavers. We were told that they had never heard that term before. It seemed as if Khes was the same for everybody else as it was for us — a cotton fabric patterned with stripes and plaids. The third week was coming to an end and we had to wrap things up before flying back to Ahmedabad, so we took our disappointment in our bags back to my home in Jalandhar and started compiling our field notes. The next thing we know, my mother had found a fabric in an old trunk at our home and she brought it to us saying, “This was something your grandfather used to call a Khes and he never really let anybody use it. It was really precious to him and is quite old, probably before the time of Partition.” We had a look at that fabric and there it was, a double cloth patterned Khes. We had finally managed to locate a Majnu. And then it struck us – the Punjab that we know, is not the Punjab that had been, it is only one bit of it. What if this particular type of Khes was never woven in the parts of Punjab that are right now in India?

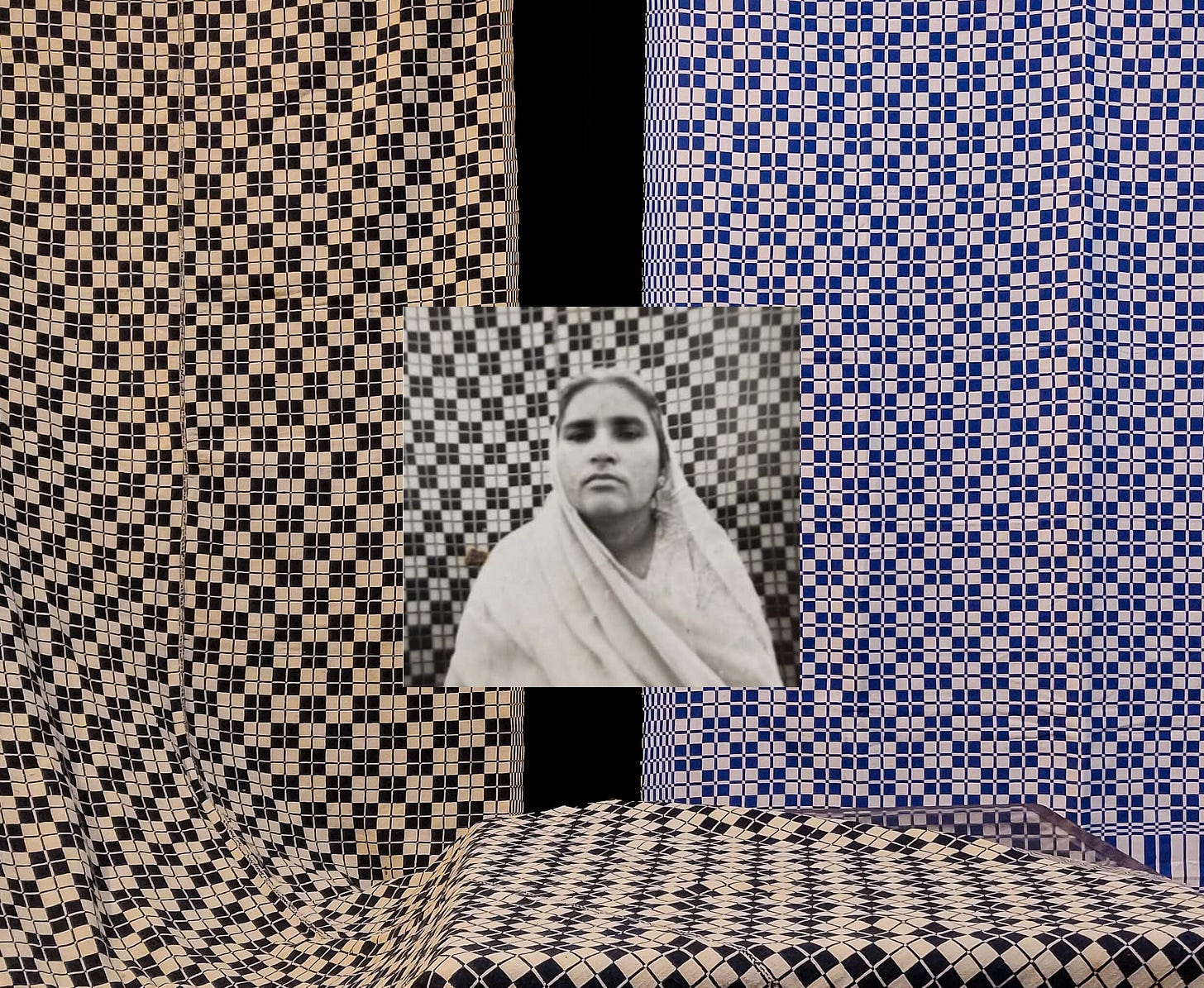

Next, we started reaching out to all the elders; family members, family friends, neighbors, everyone. And as it turned out, almost all of them knew about Majnu Khes and some even owned a few pieces. The only commonality between these people who owned Majnu pieces was that they had migrated from West Punjab (present-day Pakistan) to East Punjab (present-day India) during the exodus of 1947. Having established that Majnu Khes was being made nowhere in India and that the only pieces left are those select few that people managed to get with them while they migrated, we wanted to know if Majnu was still being woven in Pakistan. With the help of our faculty members, we got in touch with Noorjehan Bilgrami, an artist and textile researcher from Karachi, also a founding member of the Indus Valley School of Design, and we spoke to her about our findings on the subject of Khes. She further put us in touch with Zeb Tariq, a former student of the College of Art, Lahore, who had researched Khes for her thesis in the late 90s. Zeb was kind enough to share her research document with us, which introduced us to many different visuals that were used in patterning the Majnu Khes. But even they were not sure if Majnu was being woven in Pakistan anymore or not. In the meantime, we had reached our academic deadline for the submission of that project, and we had to stop working on it. But we knew that there was much more left for us to unravel. So with that, our classroom project ended in November of 2018, and The Khes Project began.

We took it ahead as our graduation projects that began in January 2020 and started finding more about Khes and locating its connection to the partition of the subcontinent. We realised that overall, there were three types of Khes – Saada, Gumti, and Majnu – based on the intricacy of the weave structure involved in the making of the fabric. For the textile enthusiasts or people who have studied weave structures, Saada Khes uses twill weave, Gumti uses float-based derivatives of plain weave paired with a striped colour arrangement of the warp and the weft, and Majnu, as mentioned earlier, uses the most intricate structure of all three, double weave / double-cloth. Our focus was on the Majnu Khes for two reasons; one, it was the particular Khes that we didn’t know much about, had never used as kids, and was basically something that we were not familiar with, two, it allowed us to tap into the narratives of Partition and hence, into the histories of our own families who had migrated from West to East Punjab during that time.

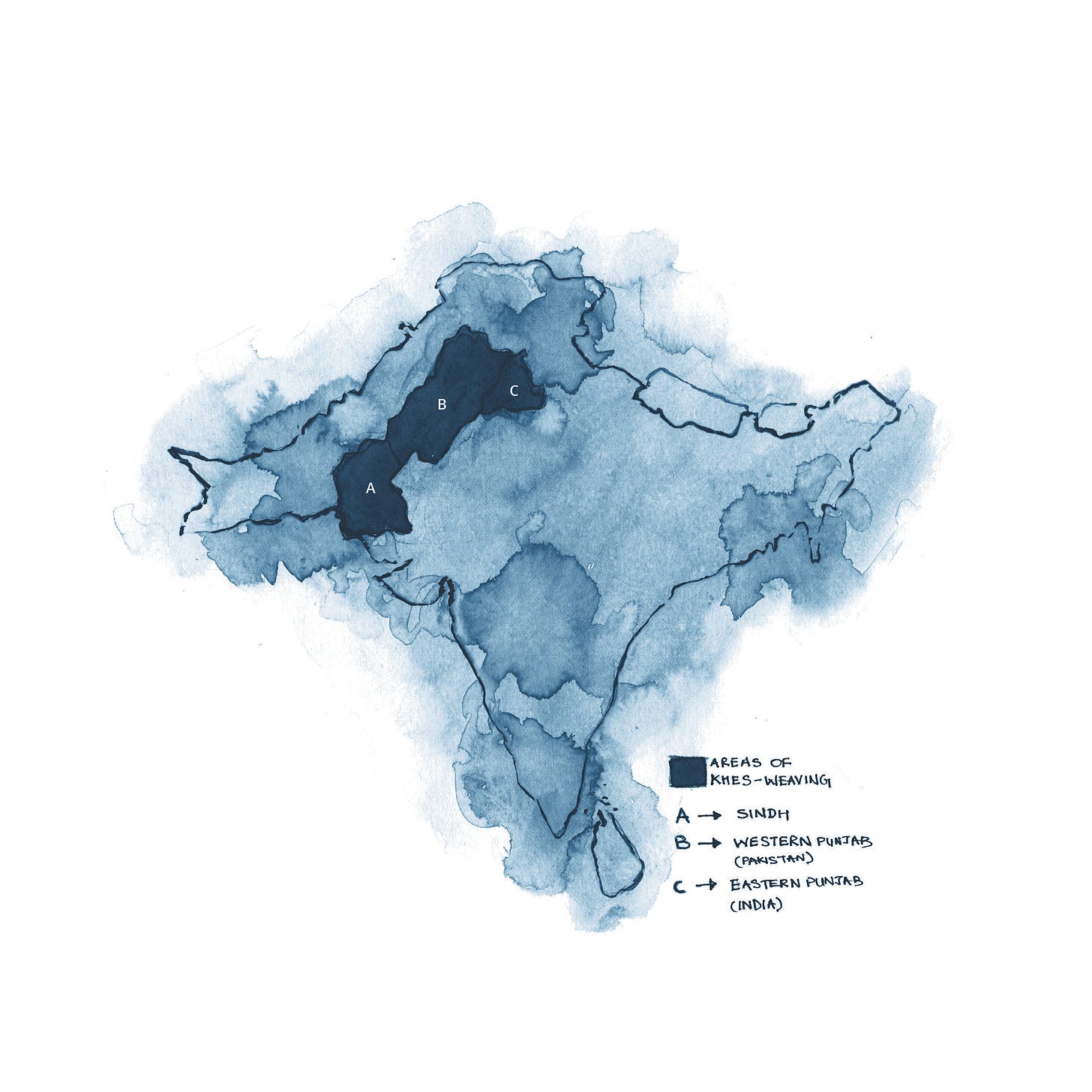

We started interviewing Partition migrants and documenting the Khes pieces they had managed to bring with them. Before Covid-19 took over the world, we managed to record a few stories about Majnu Khes and Partition and photograph the pieces that we had encountered. In a conversation with Satinder Kaur, who was thirteen years old during Partition, she told us that in her home in Hafizabad, they had almost a hundred Khes pieces, which were bought or made (at home by the mothers and grandmothers) for the general use and the dowries of all the daughters of the house. She mentioned how the skill of the Muslim weavers of that time was unparalleled, and hence, finding Majnu Khes pieces like the ones that we had documented, was next to impossible. That got us wondering, had the Muslims not been forced to leave East Punjab, would the practice of Majnu Khes weaving be still alive in India? Khes weaving took place across the entire belt from Sindh to West Punjab to East Punjab, and the intricacy of the weave decreased as one moved towards East Punjab. Prior to Partition, there was a flow in the textile market across this region, but once the Radcliffe Line materialized, it stopped. And hence, Majnu Khes ceased to be a known entity in the households of East Punjab.

In another conversation with Joginder Kaur, who was seven years old in 1947, she told us about Majnu being reserved for special occasions, or for guests, “Whenever some guest was supposed to be at someone’s home, people used to put the entire fabric on the divan in the living room, to show that special arrangements had been done.” Even Tejinder Kaur, another of our interviewees, said the same. While speaking to her, we showed her images of Majnu Khes and she informed us that this used to be a special fabric with intricate designs, “vo khas hota tha (it used to be special)”. This could also be because Majnu Khes was a commercial craft. It was never, or rather could not be practiced as a home-based craft because of the intricacy of the weave involved in the construction of the fabric. Unlike the simple Sada Khes, Majnu required a professional setup of a complex loom mechanism, which is why it could not be done at home like Dhurries and Sada Khes. It had to be bought from the Julahas, the village weavers, and hence would have been more expensive and not accessible to all. As a result, it would have been of greater value to people. Also, sometimes, the yarn for Majnu used to be spun by mothers at home, and then sent off to the weavers for weaving. This was another factor that added value to this textile.

Meanwhile, we were back in touch with Noorjehan Bilgrami, who further put us in touch with Iram Ansari, in Lahore, and Sohail Tareen in Multan. Both of them work with textiles, while Iram Ji owns a studio, Sohail Ji owns a textile manufacturing unit. They both informed us that whatever is being produced, in terms of Majnu Khes, in Pakistan, is being done on power looms, and the quality of the fabric has gone down as compared to what it used to be when the same fabric was being produced on handlooms. Both Noorjehan Ji and Iram Ji mentioned that Majnu Khes was one of the major textile productions of village Ambh in the Pakistani province of Sindh, but it is not being done anymore. With their help, we're trying to get a few Khes pieces woven in Sindh and Multan for an exhibition that we had planned as the end product of our graduation projects, which never went through because of the pandemic. However, we did manage to get a few pieces woven in Pakistan. Some of the weavers who work for Sohail Ji were traditional Khes weavers, and although now they only work on power looms, they agreed to weave a few Majnu pieces on handlooms for our project. And through Iram Ji, we were able to get some samples done by Rasool Bakhsh, a Lungi weaver from Ambh. We sent across the designs and close up of the motifs that constituted the Majnu pieces we wanted to archive, and they were able to weave just what we had expected! There was an issue though – getting these textiles to India, as there is no way to courier directly from Pakistan to India or vice versa. So one package came via Dubai, and the other came via London. Funny to think that while Lahore is just a few hundred kilometers away from Jalandhar, the textiles had to be sent to London before they reached Delhi and then finally Jalandhar. How we wish there was an easy way to make that journey to Lahore, that wouldn’t even last more than four hours, without any complications.

It has been almost four years now since we started researching Khes and discovering its history and listening to its stories. Khes, for us, is no longer just a textile craft. It has become a medium to strike conversations on artificial political divisions of cultural zones. We wish to build a platform where people can have discussions about their past with so many others who have similar stories to share. Sometimes we wonder what it would have been like if back in 2018, our faculty hadn’t pushed us to research closer to home for that classroom project, had we not discovered Khes, and what our work life would have been like. All we know is that we are grateful for how things turned out to be because it gave us a chance to look back into our own history, the trauma our ancestors lived through, and speak about it to others like us. It made us realise the power of textiles and how they can come through as a platform to discuss syncretic traditions that once were and have been lost now, all because of a synthetic division of one people, led by political propaganda, that was supposed to put an end to religious intolerance, but has somehow alienated us from our own.

Credits:

Arjunvir Singh and Rashi Sharma are textile design graduates from the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad. They have been researching the textile tradition of Majnu Khes, and its various aspects along with Partition’s impact on it, for the last four years. Their work in this regard can be seen at The Khes Project.

Individual handles: @arjunvir.s @rashisharma04

Image credits: Arjunvir Singh and Rashi Sharma

This article is meaningful and timely. My mother passed away a month ago at the age of 91. She had two khes in her highly curated belongings. I knew they were important to her because she told us her father (my nana) had valued them. My sister kept one. I have the other and was planning to take it to a local textile museum in the USA with hopes of learning more about it. Thanks to you, I know these pieces are Manju Khes! I’m guessing they were brought from Lahore (my mother’s birth place) to Nurpur, HP (her ancestral home) just before partition. When she married and immigrated to Canada, they came with her. She kept them when moving to the US in 2015. These khes must be around 75 years old and are in excellent condition. As part of the Indian diaspora I feel unmoored after my mother’s passing. Thank you for filling in this missing link in our mother’s story.

Kudos Rashi and Arjunvir

Indeed ‘Awesome Khes project research with strong details. Well done. 👏👏