European Symbolism in Mughal Art: The Pietre Dura Panels of the Red Fort

Words by Aqsa Ashraf

Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labour of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com. Check out our Shop and our Podcast. You can also follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

European Symbolism in Mughal Art: The Pietre Dura Panels of the Red Fort by Aqsa Ashraf

Agar firdous bar ru-ye zamin ast,

Hamin ast-o, Hamin ast-o, Hamin ast

If there is Paradise on Earth,

It is this, it is this, it is this.

Emperor Shah Jahan had this famous Persian couplet inscribed on the walls of the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audiences) in Delhi’s Red Fort. The Mughals, a late-medieval dynasty that ruled India and parts of Central Asia, claimed to be of divine origin as a means to gain legitimacy. This sensibility had seeped into every aspect of their culture, including art and architecture by the mid-17th century. Shah Jahan was the fifth Mughal emperor, whose reign marked a classical age of architecture. However, unlike in the reigns of previous emperors, his reign also saw an increasing social hierarchy, and the attainment of a nearly semi-divine status of the emperor. However, it is noteworthy that Shah Jahan had inherited a rich legacy of Mughal culture from his predecessors, which needed to be maintained and added to. By the 17th century, the Mughal empire rivalled the Ottomans and the Safavids in terms of artistic and cultural developments, and these three dynasties were the leading powers of the Islamic world. In the subcontinent, however, the people that Shah Jahan ruled were diverse, as was his own court – another legacy of his ancestors. As art historian Ebba Koch argues, the sustenance of the empire was dependent on appeasing to this diverse group of people, and that in turn depended on the emperor’s charisma as well as the myth of his kingship. In other words, Shah Jahan was required to ensure not just his role was that of the emperor of Hindustan, but also that of a universal emperor. The following essay analyses the means that Shah Jahan adopted to achieve this, with a particular focus on mystical allegory employed in the art and architecture of the Qila E-Mubarak (Blessed Fort), or the Red Fort, as we know it today.

Before Shah Jahan, the Mughals had largely ruled from Agra. However, in 1648, a new capital was built in Delhi by Shah Jahan, called Shahjahanabad, which we now know as Old Delhi. Perhaps the most important feature of its building process was the use of paradisical themes in the layout and architecture of the Red Fort. This wasn’t unique to Shah Jahan’s reign, but had been used by all previous Mughal emperors. An inscription near Shah Jahan’s sleeping quarters compared his creation of the Red Fort to a mansion in paradise. The gardens in the fort were made to resemble the Chahar-Bagh, or the four gardens of Paradise. The Nahar-e-Bahisht, or the Stream of Paradise, sourcing its water from the river Yamuna, flowed through carved channels in the fort. Besides, Delhi was a particularly suitable space for constructing the new capital, as it had been the seat of many Muslim rulers before, and itself had the heritage of six cities before Shah Jahan added his own to it. However, apart from just adopting Islamic themes to construct the capital and its fort, Shah Jahan also adopted art and architectural features from Central Asia and Europe. These influences included the Chatta Chowk, a covered market which was the only one like it in 17th century Hindustan, but was fairly common in Central Asia. Even the canal flowing through the Chandi Chowk (Moonlit Square) was inspired by an older canal built in Isfahan. Europe, and particularly Jesuit influence had been prominent in the Mughal court since the reign of Akbar. Shah Jahan, despite the relative rise of orthodoxy during his reign, adopted European symbolism while building the Red Fort, such as in the marble throne of the Diwan-i-Am (Hall of Public Audiences). Historians Cynthia Talbot and Catherine Asher write that the bulbous columns present in the throne were inspired by the illustrations of holy spaces in European Painting. Additionally, they were unique to his reign, because European motifs were only found in the paintings of previous Mughal rulers, rather than their architecture.

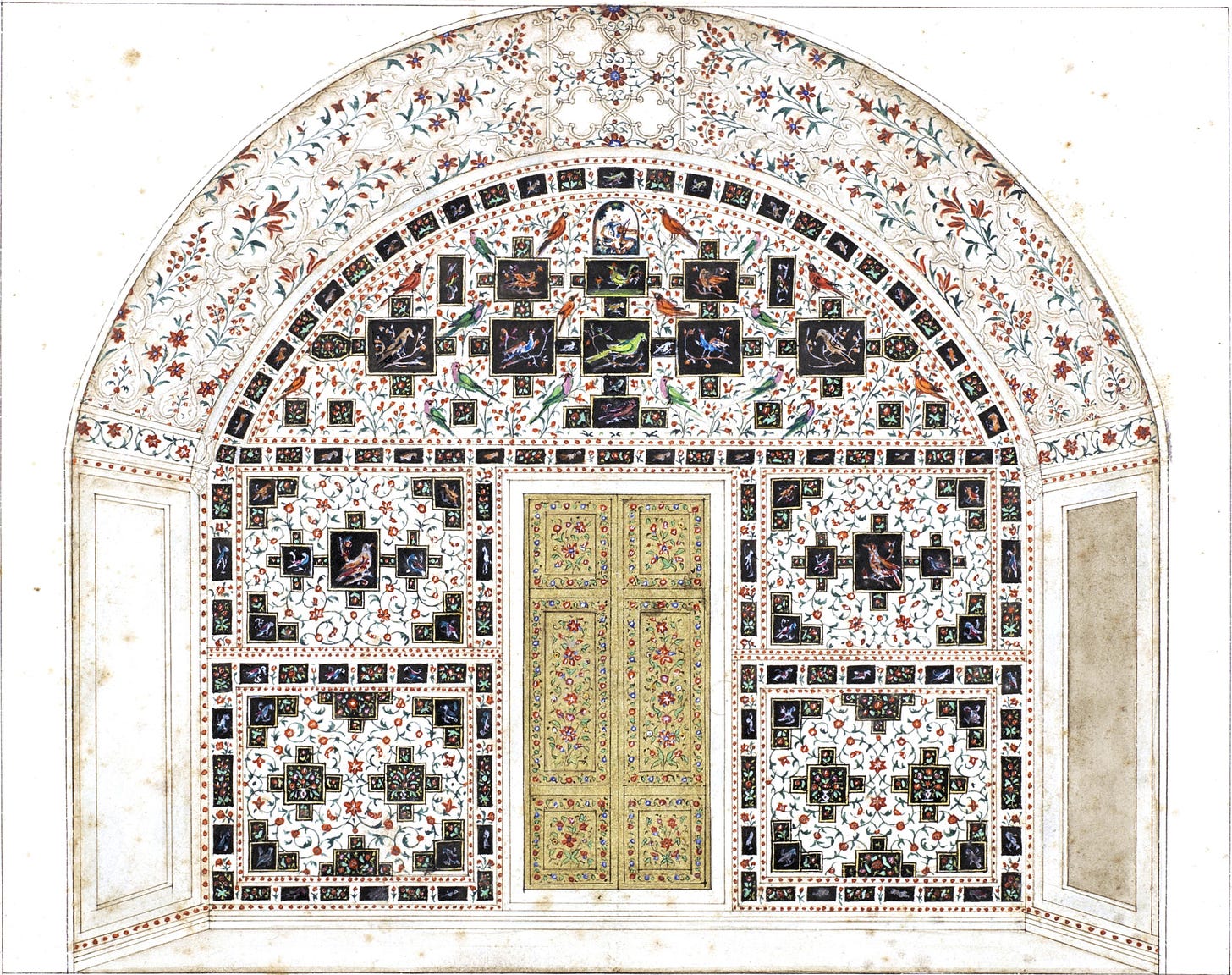

More interesting perhaps are the Italian Pietre-Dura panels behind the marble throne. Such panels were popular in 17th century Florence, and by Aurangzeb’s reign, had become common in the Mughal court too. They were initially employed in Medici tombs, and as gifts from the Medici family to other royals, although they were also used on mobile objects like cabinets. The panels in the Red Fort numbered 318 in total, and were probably made by Austin de Bordeaux, a jeweler. They depict Orpheus playing his lute, as a lion, a hare, a dog, a deer and leopard listen enraptured at his feet. Underneath are several other panels illustrating European birds, flowers of many kinds with butterflies hovering by, as well as small lions. Orpheus is a popular character in Greek mythology, whose songs feature in the Metamorphosis of Ovid. He was given the extraordinary gift of charming the living and the non-living alike with his music by the god Apollo. When he died, his lyre was immortalized as a constellation. The placement of such art in the Diwan-i-Am behind the emperor’s sitting place is particularly significant, because it was a hall of audience accessible to the general public, where the emperor would hold durbar twice daily, and the European symbolism therefore acted as a part of Mughal propaganda of divine kingship. Ebba Koch has worked extensively on the Orpheus panels of the Diwan-i-Am, and according to her, the motif was carefully chosen because it has parallels with Islamic mythology. Like Orpheus, the prophet Suleyman was said to be able to communicate with animals and birds in a way that ordinary people couldn’t. Additionally, Suleyman was a king, and Shah Jahan, through this allegory, attempts to appropriate his semi-divine status. A motif that was quite popular in Shah Jahani paintings and architecture is that of a lion and a lamb resting together, which symbolized the justice that prevailed in Shah Jahan’s reign, allowing the weak and the strong to live together. This too has similarities with the justice of Suleyman and the way animals of prey sit peacefully with their predators in the Orpheus panel.

These panels were painted in a miniature painting by Ghulam Ali Khan in the 19th century, and later, in 1845, by Company Artists. Before the Revolt of 1857, a Mr. Beresford describes the panels in his Delhi Guide, the description is quoted in an 1876 work by Carr Stephen called The Archeology and Monumental Remains of Delhi. Beresford, that the “whole of the wall behind the throne is covered with mosaic paintings, in precious stones of the most beautiful flowers, fruits, birds and beasts of Hindostan”. However, a majority of these panels were pilfered during the Revolt of 1857, when the British plundered the Red Fort of all precious objects that could be carried off. The few that survived were either too high up for the plunderers to reach, given that the wall is 8 foot high, or were badly damaged. Carr Stephen writes that the panels were taken to England in 1857 by an officer of the Delhi Field force and placed in the Kensington Museum after being bought by the British government for 500 pounds. In the late 19th century, when Lord Curzon became the Viceroy of India, he ordered that the panels be brought back from Kensington Museum and reinstalled in the Red Fort, for his Durbar, which was to be held in 1903. The restoration was only possible because of the drawings that existed. Additionally, all of the panels weren’t present to be restored, and therefore new panels were put in their places using the same stones, made by European artists. The restoration work was completed in 1909, and what we see in the Diwan-i-Am today is the result of Lord Curzon’s attempt to hide the “vandalism of an earlier age”.

The art history of the Indian subcontinent throws ample light on the cultural assimilations that took place over history, and therefore are an excellent example of the plurality of heritage. The Pietre-Dura panels of the Red Fort, in particular, have a history that goes back to Akbar and Jahangir’s fascination with European motifs, and an even earlier fascination of the Mughals to portray themselves as universal rulers. The Red Fort was built with the intention of it being the grandest, biggest Mughal fort, and was completed after nearly nine years and a painstaking attention given to detail. The panels, therefore, are so much more than their beauty’s worth. They were as much a symbol of power as the hall of audience they were placed in. However, as with so many other symbols of power in the Red Fort, and indeed the whole of Shahjahanabad, their meaning changed. For the plunderers, they were beautiful objects of loot, evidence of the British conquest of Delhi, and the defeat of one of the most powerful Hindustani dynasties to have ever existed. In other words, they were evidence of an end of age. Although they were restored by Lord Curzon after fifty years of being looted, it had more to do with the British image of vandalism rather than their in-situ preservation as historical artefacts. Their restoration marked the beginning of another age, and the complete distortion of their meaning.

Credits:

Aqsa Ashraf is a student of History. She loves art and mythology, and appreciates the cultural exchanges that have happened throughout the past.

References:

Asher, Catherine B., Talbot, Cynthia; India Before Europe. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Koch, Ebba; Mughal Art and Imperial Ideology: Collected Essays. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Koch, Ebba; The Mughal Emperor as Solomon, Majnun, and Orpheus, or the Album as a Think Tank for Allegory. Muqarnas, Vol. 27, 2010.

Safvi, Rana; Shahjahanabad: The Living City of Old Delhi. India: Harper Collins, 2019.

Stephen, Carl; The Archaeology and Monumental Remains of Delhi. Ludhiana: Civil and Miliary Gazette, 1876.