Ghost Stories in the Room: Stories that Migrate in/to Urban India

Words by Azania Imtiaz Khatri-Patel

Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labour of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com. You can also follow us on Instagram and Twitter. You can also follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Ghost Stories in the Room: Stories that Migrate in/to Urban India by Azania Imtiaz Khatri-Patel

Mehruinsa sat in the centre of the Slum Rehabilitation Association (SRA) flat, occupying the rickety plastic chair like a throne. As the matriarch of a family six - all residing under the same government constructed roof- she has the world weariness of someone who has seen the struggles of many years - and is finally ready to rest.

She rested her legs on a make-shift footstool complained of how her feet would swell up – ‘like tree trunks’ she gesticulated as her daughter-in-law brought me a glass of sticky, orange Mirinda on a melmoware tray. I had refused the offering in the first two instances- my desi sensibility reminding me a third refusal would be constructed as grave indolence. A guest in her house, I had no intentions of offending Mehrunisa. This would have been a common outtake from a weekend evening in Mumbai, India- if it were not for the particularity of circumstances.

It was 2019 and I was working on my academic dissertation. I was here for research – and Mehrunisa was going to tell me a ghost story.

Mehrunisa told me that her family had moved to the city three generations ago. Before that her grandmother was a mid-wife. She honed her skills in helping women in labour. It was a noble calling. One night- my storyteller narrated- tumultuous rains took their previous town by storm, swallowing thatched roofs and forcing waves beyond the shoreline. A loud knock shook the door of their kaccha makkan (tr. Informally built house.) A tall man beseeched her to come with him- his wife was in labour. The Midwife was bound to her duty. She would help the man.

As she followed him out- from the thin alleys of their township towards the nearby dongar (tr. hillock) , the man seemed to grow in height. With terror, she realized, this wasn’t a man- but a Djinn. She followed him anyway- greed sinking in. A supernatural creature would give her miraculous dues for delivering his child safely. She followed him into a cave- finding a giant woman heaving in labour.

After she delivered the non-human baby, she asked the father for her wages. The Djinn nodded and asked her to pick up as many fallen leaves of the Peepal tree nearby as she could. Irate but afraid- she did as she was told. She carried the pile of leaves- grumbling all the way home. She felt cheated- and didn’t hold the leaves tight, dropping most of them on the path. When she returned home, her husband asked her what had gone down- as she recounted, she waved the single Peepal leaf that remained with her in annoyance- only to realize it had turned into pure gold.

In cultures that rely heavily on orality, such as the South Asian ones, our stories carry history. They carry morals, teachings and generations of experience. Often times, stories also home trauma- they demand to be articulated, and to let out in the world. As the folktale collected by AK Ramanujan goes - a woman knew a story and a song - and she never shared them to the world. Suffocated, they chose to ‘turn’ into a pair of coat and shoes - and leave her.

To not share our stories is to forget them.

My project in Mumbai’s SRA societies sought to collect the stories of people on the urban fringe. In Mumbai, a whooping 41.3% of the population resides in slums and the SRA housing projects run by the government aim to improve the urban conditions of living. What policy frequently ignores is that slum residents are often invisible on voter records, formal documentation in ways that mean they can have their own voices and grievances heard. A majority of slum residents are migrant workers, and form the invisible backbone of cities. In the anonymity they are entrenched in, stories of ghosts, miracles, saints and the surreal are often their only links to a full bodied identity.

My father’s family grew up in a Mumbai Slum, in fact the same one which was razed to build the apartment complex that Mehurinsa’s family now occupies. Called Squatter’s Colony, this area was recognized less by its people and more by their ‘criminal act’ of seeking shelter in a cruel city. My grandparent’s had migrated from rural Gujarat- dada abba working odd jobs in sweet shops and manual labour and artificial jewellery making to fend for his family in a foreign city. As internal migrants- they carried very little into the shanty house- with the exception of meagre wedding gold, a cloth bound Quran and mythologies from ‘back home’.

Back home was the village- back home was where we were descendants of a great Sufi peer (tr. Saint) and not exhausted daily wage labourers. The tale of magic they brought to Mumbai was one of venoms and divine immunity.

The Saint who was an ancestor was once a young man- with the desires of a young man. He fell in love with a married woman in an unhappy marriage. She loved him back- their families would not let them elope. The woman’s husband learnt of her deceit- and to stop her lover once and for all- he buried stolen goods in the Saint’s farm land- and reported him to the colonial police. Caught for a crime he had not committed- humiliated even after he was let go with a stern warning – the saint decided to give up on the world and sit in a deep mediation.

He mediated so deeply that the earth began to boil up- snakes and scorpions were forced out of their burrows. The Leader of the Snakes asked the Saint to pause in his mediation- he vowed that any who shared the Saint’s blood would be immune to the venom of his kind if the Saint let them return to their burrows. The Saint agreed.

My family has held on to this belief of miraculous immunity through generations. It has crossed villages with marriage- and gotten on to squalid trains to Mumbai and Delhi- and indentured ships to South Africa. It took a long haul flight with me from Mumbai to London two years ago. The miracle (its truth valence irrelevant) has migrated across space and time.

When we lose our homes- whether out of social or economic dispossession – our stories promise us herodom and become a source of courage. Stories are powerful because they allow those who are otherwise forced into silence to give words to their affect. Ethnographies have discussed in detail how backward class and caste groups along with religious minorities often experience ‘possession’- that is occupation by ghostly entities in times of social strife.

What are ghosts if nothing but stories that cannot remain buried?

Anna Tsing talks about how every landscape is haunted by past ways of life. Bodies of urban migrants are perilous terrains, then. In Avery Gordon’s work, ghosts often represent intersections of societal tension, violence and oppression. South Asian cities are full of stories of industrial trauma and deep loss. One of the societies I worked in was near the site of a former stone quarry. Physically demanding and unsafe, many of those who lived here were children and grandchildren of people dismembered or killed due to unsafe work conditions.

It is no surprise then that the most popular ghost story in this area is of Ratnaben- an apparition who appears at odd hours of night. This ghost has only one arm and one leg- urban legend goes, she is the spirit of a woman who was crushed under quarry machinery.

In 2020, with the pandemic consequent lockdowns- visuals of migrant mass exoduses were common place. The hysteria birthed an unsettling realization – even after living in cities for generations- migrant workers do not see it as home. They do not see the urban as safe or a community to rely on. They are painfully aware of their own invisibilization. In cruel irony, many news articles referred to the victims of this exodus as the ‘ghosts’ of the lockdown. A particularly poignant articulation portrayed these migrants as ‘ghost mutineers in search of a home’.

From articulating their own stories as a mutiny against invisibility to being rendered spectres themselves, the internal migrants of urban India occupy perilous liminal spaces. They histories are not commonplace and their sense of belonging in perpetual question.

As I think back to Mehrunisa, I think back to her willingness to tell me the story she homed for generations. I think of her grandson’s piqued interest. I think of stories that demand to be told. I think of the anxieties and grief and the trauma that haunt the walls of squalid SRA houses across the country.

What are our histories then, if not the ghosts that we cannot afford to exorcise?

Dedicated to Mehrunisa, Imtiaz, Ismail and the souls that lived a little less so that their generations could have the world and left too early - with many stories untold.

Credits

Azania Imtiaz Khatri-Patel is a Rhodes Scholar in Residence at the University of Oxford. She researches ghosts, haunted houses (literal and metaphoric) and falls in love with cities and words too often. She is currently pursuing a Master's in Public Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government and moonlights as a writer of fiction, creative nonfiction and long form journalism. Her Instagram is: @azania_patel

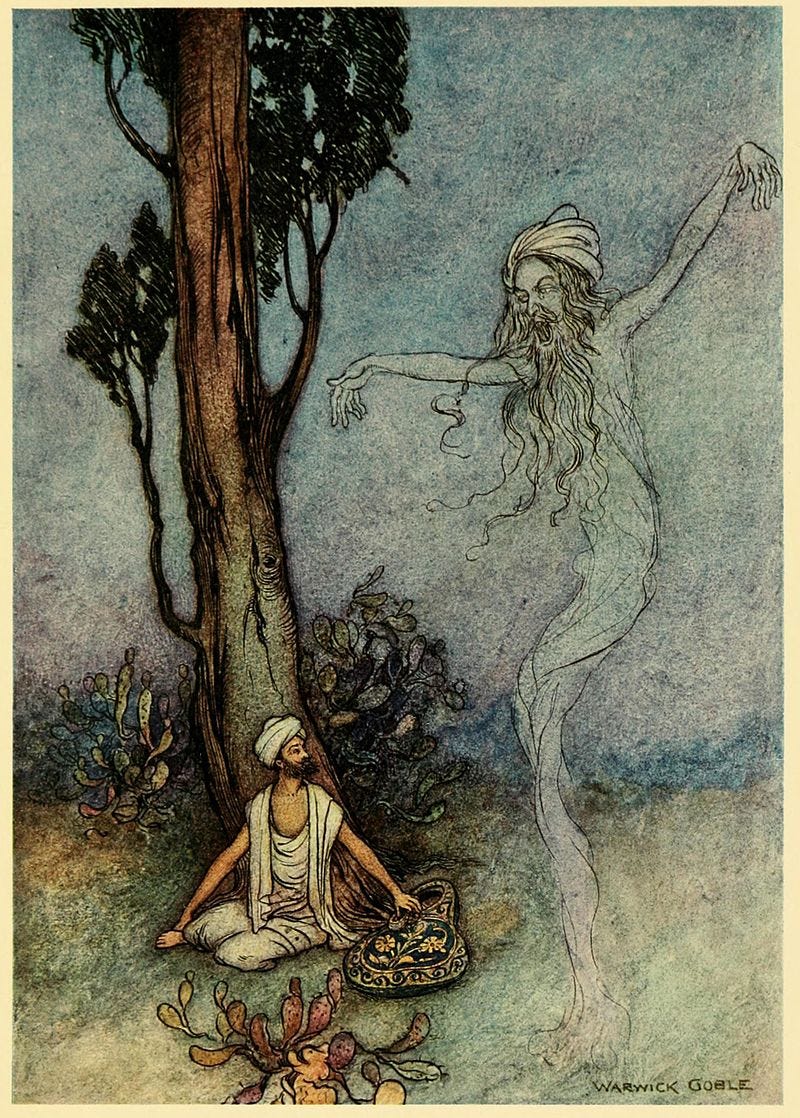

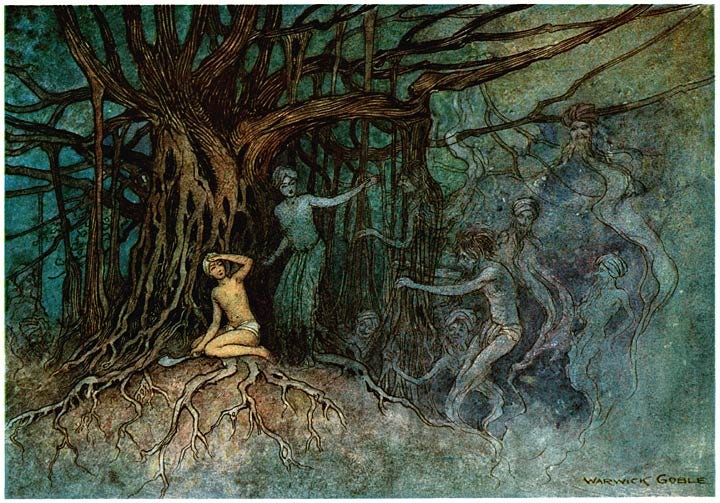

Illustrations are done by Warwick Goble which taken from the book Folk-tales of Bengal by Lal Behari Day, published in 1883.

References

1 Kambar,C. (1994). Oral Tradition And Indian Literature. Indian Literature, 37(5 (163), 110-115.

2 Ramanujan, A. K. (2020). A Story and a Song. In A Flowering Tree (pp. 1-2). University of California Press.

3 Government of India. (2011). National Census (India, Ministry of Home Affairs, Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner).

4 Opler, M.E. (1957) Spirit Possession in a Rural Area of Northern India In Portraits of Religious Systems (pp. 553-566) Retrieved from http://danbhai.com/anthro_of_hinduism/opler_spirit_possession_in_a_rural_area.pdf

5 Tsing, A., Swanson, H. A., Gan, E., & Bubandt, N. (Eds.). (2017). Arts of living on a damaged planet. Minnesota, United States of America: Univ Minnesota Press.

6 Gordon, A. (2011). Ghostly matters: Haunting and the sociological imagination. Minneapolis, United States of America: University of Minnesota Press.

7 Ray, M. (2020) "Ghosts in Search of Home." the Telegraph Online (online) https://www.telegraphindia.com/opinion/ghosts-in-search-of-home-the-covid-19-migrant-exodus/cid/1782028.

What a beautiful read!!