Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labor of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to check out our SHOP and our Podcast.

Heera Mandi: The real story behind Lahore's Red Light District

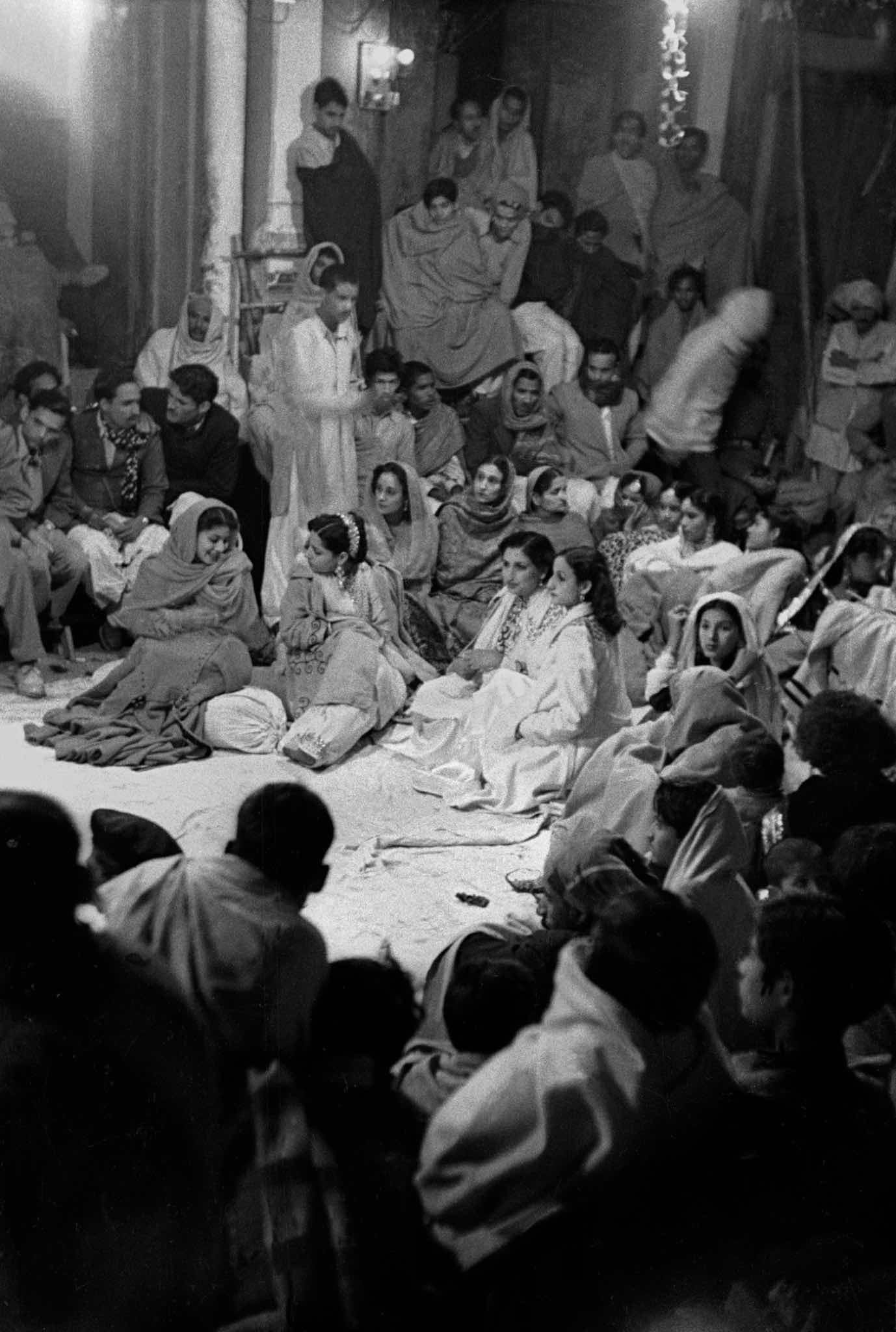

You walk into a cavernous room, covered with dazzling mirrors, sparkling in the candlelight and hung with tapestries and velvet curtains. The arched ceilings are tiled with colorful ceramics, and are supported by carved, marble columns with brilliant chandeliers hanging between them. Everything has a golden sheen and the air is scented with flowers. You take a seat on a padded rug while invisible hands deliver a hookah to your side. Settled in the back of the room are musicians, beginning to play a haunting song on their tabla, pakhawaj, sarangi, and bansuri. A duffli joins in as several veiled women gracefully enter the room, the bells on their ghungroo chiming on beat, their hand-embroidered dresses and lavish jewels catching the candlelight. You watch, mesmerized, as they begin an intricately choreographed dance, dresses swirling as their veils are lifted, revealing the most beautiful women you have ever seen. You are in a 17th century Mughal mehfil, blessed to witness the sophisticated mujra of the elite tawaifs of Heera Mandi.

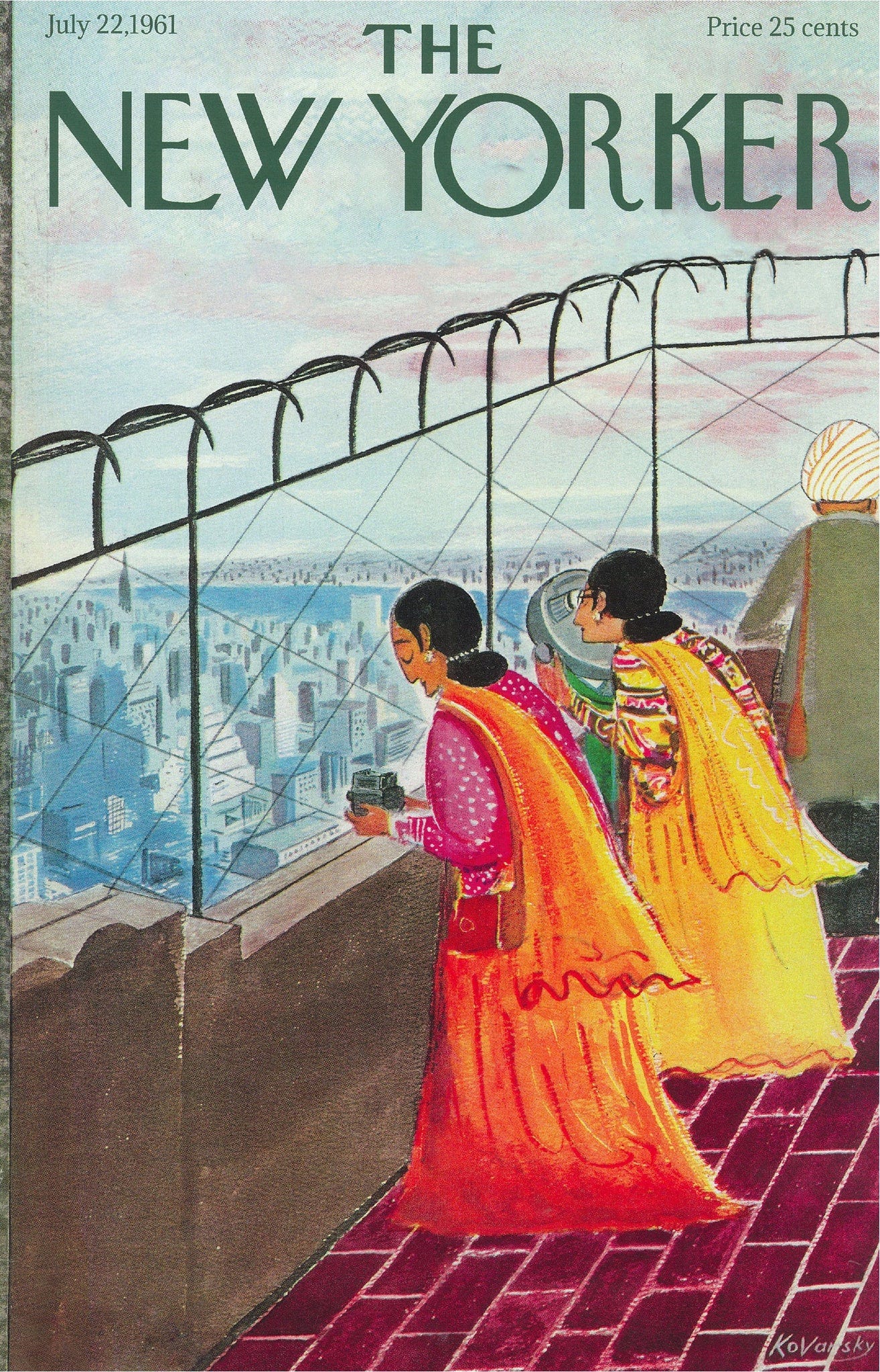

I was born and brought up in the Canadian education system, within which we only had two glimpses of Indian history in high school, briefly, in an elective ancient civilizations class when we skimmed over the under documented Indus Valley to get to the much more ‘exciting’ Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, and then as an anecdote to a lesson on WWII, when we were discussing the fallout from the war and half-heartedly watched a short documentary about Gandhi and peaceful protests. We were busy, because the next day was the 1920s, and we could wear flapper headbands and pearl necklaces over our stiff Catholic school uniforms; India’s fight for independence immediately forgotten, and Partition summarized in a single sentence.

For so long, these black and white images of South Asia in turmoil post-WWII were all that glimmered in my mind when I thought of Indian history. The University of Toronto’s St. George campus, at the time when I was an English and History undergrad there, did not offer any South Asian history courses even though I had really hoped to take them, so I studied European history, focusing on the Renaissance.

That was my impression, of course, before watching Sanay Leela Bhansali’s historical films. I never would have associated the rich, mystical imagery he produced with films like Devdas (2002), Saawariya (2007), Ram Leela (2013), Bajirao Mastani (2015), Padmaavat (2018), and Gangubai (2022) with the India of my high school classes. I do realize that historical accuracy is liberally shafted for drama, glamour, and modern aesthetics, but it does not take away from the majesty he applies to pre-colonial (or colonial-adjacent) India. Recognition must also go to director Ashutosh Gowariker’s Jodhaa Akbar (2008), which left a deeply searing image of the 16th century Mughal Empire. Now when I think of India’s history, it’s not only 20th century war photography, but sparkling forts, Mughal emperors, courtesans decked in stunning textiles and jewels, and above all, a richness in culture that I could spend a lifetime studying.