How British Colonizers used Photography to Justify the Occupation of India

Words by Tehsin Pala

Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labor of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to check out our SHOP and our Podcast.

How British Colonizers used Photography to Justify the Occupation of India

In South Asian classrooms, many textbook chapters on colonial history unfold the realities of life under British colonial occupation. Often, a few photos scattered around in the books capture the attention of distracted kids, urging them to look at the faces of their ancestors. The photos showcase a vast spectrum, some royals adorned with layers of jewelry and others immersed in battlefields while many others meet the camera's gaze in discomfort, conveying stories of slaughter, starvation, and impending death. The question lingers: Who was behind the lens, documenting these grim scenes?

With the advent of photography in Europe, the medium swiftly made its way to India through the lenses of British colonial photographers. Photographic societies and studios sprouted across the subcontinent, with the initial ones established in Bombay, Kolkata, and Madras. The Photographic Society of Bombay, founded in 1854, started with 13 members, including three Indians, and later expanded to 250 members by 1855.

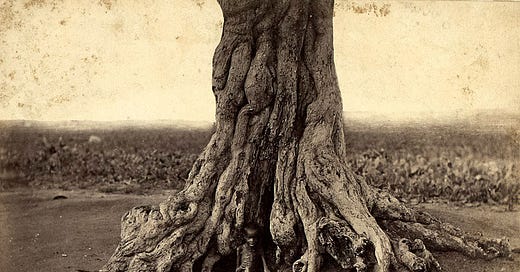

Initially, British colonial photographers focused on capturing landscapes in India through an occidental gaze. One of the initial photographers, Samuel Bourne, went on extensive tours across India to capture its diverse landscapes—a challenging task given the cumbersome camera equipment of the time. Bourne's endeavors were not propelled by his efforts or funds; they were sustained by a resource highly prized by colonials but vastly underappreciated—coolies, or low-wage Indian laborers. He acknowledged that he employed 30 coolies to carry his belongings. He sometimes beat them, and, out of callous generosity, while traveling, he even starved whole villages to feed his coolies.

Steve Edwards, in his work "Photography in Colonial India," notes that "Bourne's narratives of his journeys oscillate between an aloof distaste for Indians and a Christian awe at the landscape as a sign of God’s immensity and power." The resultant landscape photographs are a rich resource for visualizing 19th-century India. According to Bourne though, English landscapes were far superior.

Technological advancement, like photography, built on the idea of human betterment, became the facilitator of colonial projects. Biased documentation of colonial brutalities, surveillance of monarchs and rebels, and extensive ethnographic endeavors to categorize India's diverse population were unleashed through photography in many colonies, including India. The soft power wielded through captured images not only sought to subjugate and indoctrinate the Indian populace into believing their inferiority but also served as a testament, sent to Britain and beyond, to justify the perceived necessity of British civilization in what was deemed an uncivilized realm—India.

Indianize Indians

The ruling elites, upper class, and savarna (upper-caste) groups, comparatively well-off, were not immune to the impositions of colonial influence through photography. Historian Barbara Ramusack, in her work "The Indian Princes and Their States," highlighted that after 1858, colonial knowledge specifically targeted the princes and their states.

It heavily started influencing the depictions of Indian royals in portrait photography. Traditional Mughal portrait conventions, which often depicted kings engaged in battle scenes, hunting expeditions, or durbar (Mughal courts) settings, emphasizing masculinity and royal authority, began to undergo a significant shift. The advent of Western influence brought about a redefinition of aesthetic standards. Kings were now captured posing in Italianate landscapes, adopting neoclassical poses that erased the traditional Indian portrait format. To emphasize their anglicized identity, they were even paired with European-style props. The kings and royals, of course, tried to be faithful to their Indian identity, which is visible in the photographs, creating an interplay between British surveillance and Indian self-expression.

An intriguing facet of colonial influence was the contrast of Westernized backdrops with colonial attempts to further Indianize the attire of rulers. British colonials advocated for Indians to adopt a more "Indian" style of dressing, especially during significant visits of British colonial royals to India, such as The Prince of Wales in 1875-76 during the 1877 'Proclamation Durbar' held in Delhi to mark the crowning of Queen Victoria as Empress of India. In his autobiography, Gandhi noted that Maharajas felt feminized when compelled to don elaborate attire for coronation durbars. Various interpretations suggest that this behavior might have served as a form of 'othering' Indians, perpetuating a demeaning orientalist colonial gaze.

This marked the beginning of a recurring pattern where photographs reinforced stereotypes held dear by British colonials regarding Indian rulers, portraying them as ostentatious and linked to a perceived lack of masculinity. Some rulers became so influenced that they sought to reshape their identities in alignment with colonial ideologies, seeking approval from British authorities.

Some other rulers became furious at being treated like museum exhibits while still alive. For instance, in 1911, Viceroy Hardinge criticized Sayajirao Gaekwad III, Maharaja of Baroda, for dressing down at an homage ceremony. The Maharaja used this act to protest against colonial demands to deck up, which he deemed demeaning.

Fabricating images

The Revolt of 1857, often hailed as the first war of independence in India, took shape as a mutiny—an unanticipated assault from the British viewpoint. The conflict's remarkable intensity left the British colonial forces in sheer disbelief as Indian soldiers, joined by native rulers and a multitude of ordinary citizens, initiated a collective uprising against their British commanders. This united rebellion emerged as a potent challenge to the established authority of British colonial power.

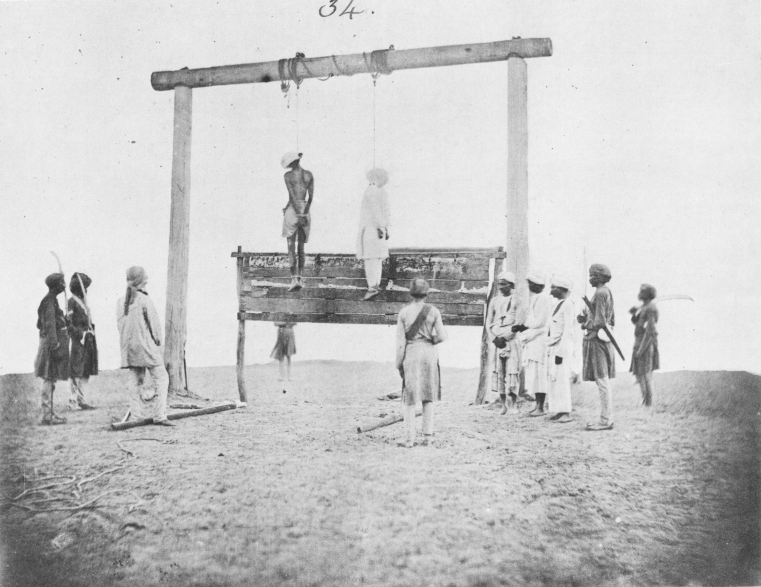

By 1858, the uprising had been brutally quelled. The retaliation by British colonial forces against the revolt went beyond brutal executions, extending to psychological and sexual abuse. For instance, upper-caste men were compelled to undertake what was considered a degrading task—cleaning blood before their death.

Photography during this period faced technological limitations, hindering the capture of moving objects, so it was difficult to capture an ongoing revolt. Adding to the complexity, many British colonial photographers faced restrictions, barring them from documenting the rebellion—an implicit admission of the British struggle to maintain control in India.

Photography became a critical tool after the rebellion, strategically wielded to manipulate perceptions, forge allegiances, and isolate the rebels. Loyalty to the British colonials found visual acclaim in works like "An Illustrated Historical Album of the Rajas and Taluqdars of Oudh" by engineer and photographer Abbas Ali. The album showcased portraits of loyalist landlords, many of whom received land confiscated from rebels. In contrast, rebels faced condemnation in other projects that repurposed existing portraits to publicly shame them and convey moral lessons regarding the severe repercussions of betrayal.