Recalling a Forgotten History of South Asians in East Harlem

Words by Sofia Ahmed

Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labour of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com. Check out our SHOP and our PODCAST. You can also follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Recalling a Forgotten History of South Asians in East Harlem by Sofia Ahmed

Alaudin Ullah teared up after the curtain closed. In front of a small audience at Columbia University he debuted his play about interracial relationships during Jim Crow. But his play, The Halal Brothers, had an unexpected story line. Ullah’s play chronicles the forgotten history of Bengali immigrants who settled in East Harlem, making sacrifices to be in relationships with Blacks and Latinos living in the community. The play is inspired by the stories of Ullah’s own family members, who were some of the first South Asians in New York City to integrate Uptown.

The stories of these South Asian working-class men who lived in African American and Puerto Rican neighborhoods in Harlem in the early 20th century runs counter to the dominant narrative that Indian Americans live in insular, ethnic enclaves as the upper class model minorities. For decades South Asians bought homes and businesses in Spanish Harlem, forming lasting relationships with other ethnic groups, an overlooked piece of history that Ullah wants shared, including stories of a beloved uncle who was instrumental in helping undocumented South Asians.

“They had a really strong knit community that was in East Harlem and that group of men married African American and Puerto Rican women,” said Ullah, a comedian and playwright. They were able to kind of be camouflaged and feel at home in Black and Brown communities.”

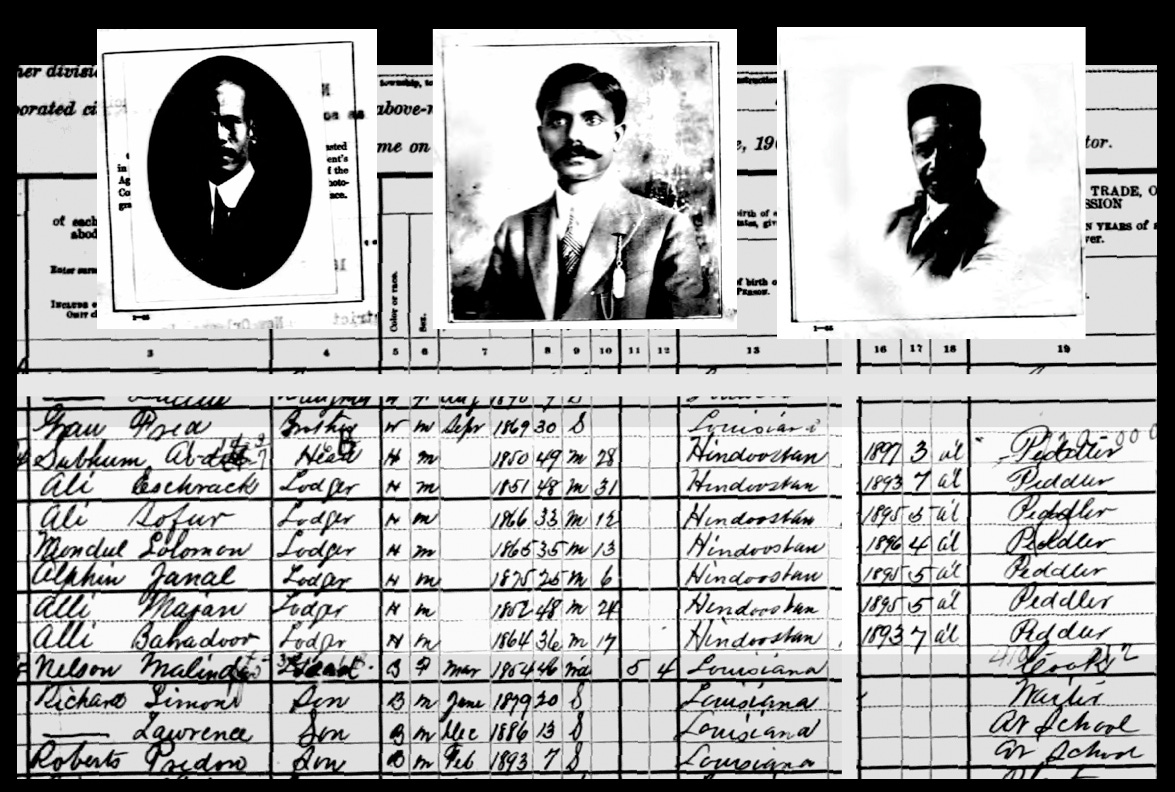

In 1917, when the United States entered World War I and xenophobia had escalated, Congress passed an immigration act that restricted Asians from migrating to the U.S. During the war, the British had Indian crewmen on their ships that traveled from India to the United States. Most of these crewmen were from East Bengal, a part of British India that today is Bangladesh.

Immigration to the United States in the early twentieth centuries is typically tied to Ellis Island. But due to the racist immigration act of the time, these men would never have been able to enter the country through Ellis Island. Instead, they abandoned the grueling work conditions on British ships to settle in New York City illegally. “There weren’t no South Asians in Ellis Island, they were jumping ship,” said Ullah. “Those Bangaldeshis had to survive undocumented, they had to be on the run, they had to learn how to live in a harsh world that wasn’t welcoming them,” said Ullah.

Because these immigrants could blend into other communities of color, it is difficult for historians to confirm how many undocumented South Asian immigrants settled in New York City. “We’ll likely never know how many Bengali speaking people intermixed with Puerto Rican, Dominican, African American and other groups, and then within a generation, lost their ties to the Banglaphone world,” said Neilish Bose, a South Asian historian and professor at the University of Victoria in Canada, who predicts thousands of Bengali immigrants could have arrived in New York between 1910-1950.

Today Ullah is a comedian and playwright. He is working on a documentary called “In Search of Bengali Harlem” with historian Vivek Bald. Ullah his family history through humorous anecdotes, doing impersonations of the accents he grew up hearing. By the time he grew up, the Bengali community that once thrived in East Harlem, no longer existed. Many Bengali immigrants returned to South Asia or moved to Staten Island, Long Island, or New Jersey, said Ullah.

Ullah enjoyed growing up in such a diverse community, he said. But the multicultural communities of East Harlem are a stark contrast with the racially insular, ethnic enclaves where South Asians live today, such as Jackson Heights, Queens and Edison, New Jersey.

“The thing about Jackson Heights or Edison is it’s very segregated and there’s no interaction with outside communities,” said Ullah. “When you segregate communities, you don’t have empathy and apathy becomes inevitable. That’s what I liked about my father and uncles. There seemed to be empathy and care about a community outside their own.”

One of Ullah’s father’s friends who he saw as an uncle was Ibrahim Chaudhry. Historian Neilish Bose describes Chaudhry as a major South Asian American historical figure. “He set up the Indian Seaman’s Club, aimed at community outreach and assistance to Indian workers and sailors,” said Bose. “He was a rare figure who worked tirelessly to aid those who were in the country at the time, and lived through the history of South Asians being denied citizenship on grounds of race.”

Ullah said Chaudhry’s Seamen’s Club was a way for him to advise Bangladeshi men working on British ships on how to settle in the U.S. “When they would take their break, they would meet there and he would help them jump ship and get organized,” said Ullah. “So by the time they would come here, they would have a place to stay, they would have a job. It was sort of like an underground railroad.”

Most of the South Asian men who migrated to Harlem lived on East 102nd and 116th streets, opening businesses, creating anti-colonial political groups and starting families, said Ullah.

“Those immigrants were illiterate. They were lost. They were isolated,” he said. “Yet they were able to become entrepreneurs, own their own restaurants, they organized. They went from dishwashers, to chefs, to owning their own restaurants.”

Ullah described Chaudhry as a superhero for changing the lives of Indian seamen who he described as “basically indentured servants” for the British. He said that he grew up seeing Chaudhry as just another South Asian uncle, but was shocked to hear about his uncle’s past, including seeing him in pictures with Malcolm X.

“I didn’t know anything about their background. It’s like finding out your parents and uncles were in the ‘X- Men,’” said Ullah. “They were creating a world where people could survive. And to even know my uncle was rolling with Malcolm is just like, what!”

Chaudhry is Nadia Hussain’s great uncle. She said said that her family was able to migrate to the United States because of Chaudhry. He organized across racial lines, something that isn’t associated with South Asians, she said.

“This idea that solidarity among working class people or people of color is new or hasn’t been done, that’s just not true. That’s a disservice to that history. Black and Brown communities have worked together to shape our country,” said Hussain.

But world events, such as World War II, changed the make-up of the Bengali community in Harlem. According to Bose, when India became independent from the British and the nation states of India and Pakistan were created in 1947, many South Asians returned to the region. “From the early 1950s, almost no traces of new Bengali migrants are found in the historical record,” he said.

Class differences played a role as well. During the next wave of South Asian immigration in 1965 and beyond, most migrants from that region were from the professional class, said Ullah. The multiracial community that existed between Bangladeshis, African Americans and Puerto Ricans dissipated. The Bangladeshi restaurants were replaced by delis and bodegas.

Today, there’s little evidence that there ever was a community of Bangladeshis in East Harlem. “There were restaurants. There were associations. There was a mosque,” said Hussain, adding that one of the last remnants of the Bangladeshi community was Al Madina Mosque, which Chaudhry founded in East Harlem, before it moved to 11th Street in 1979.

Ullah said his family story is about resilience and survival. “My uncles and my father were trying to make their communities stronger, but not at the expense of Black people,” said Ullah. “There seemed to be empathy and care about a community outside of their own. That’s something in a very white narrative of America that doesn't get to be told.”

Credits

Sofia Ahmed is a freelance writer and graduate student at Columbia Journalism School who covers labor and immigration. Originally from Phoenix, Arizona, she enjoys spending time in the sun, cooking, and writing.

Bengalis are not the same as Indians

Even in the UK, the Bengalis were always economically deprived

Most Bengali men married Puerto Rican and black women

Not to mention they don't follow a caste system which promotes colorism and status.

I don't see Bengali men having an issue with dark skin Bengali women

However Indian males routinely in newspaper ads demand fair skin women

Indian Hindu women are generally feminist and hate Hindu male treatment of Indian women.