Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labour of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com. Don’t forget to check out our SHOP and our PODCAST. You can also follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Reena Virk, Beyond the Headlines by Angel Bista

November 14, 1997, is a dark day in Canadian history. 14-year-old Reena Virk, an Indo-Canadian resident of Saanich, British Columbia, was swarmed by a group of teenagers and brutally beaten and drowned. Her murder would go on to become infamous nationally—as a tragic example of bullying and juvenile violence. The court proceedings and media coverage that followed, however, failed to capture the true nature of the injustice Virk endured—and how combined histories of racism and sexism rendered Virk’s death into a ghastly lynching.

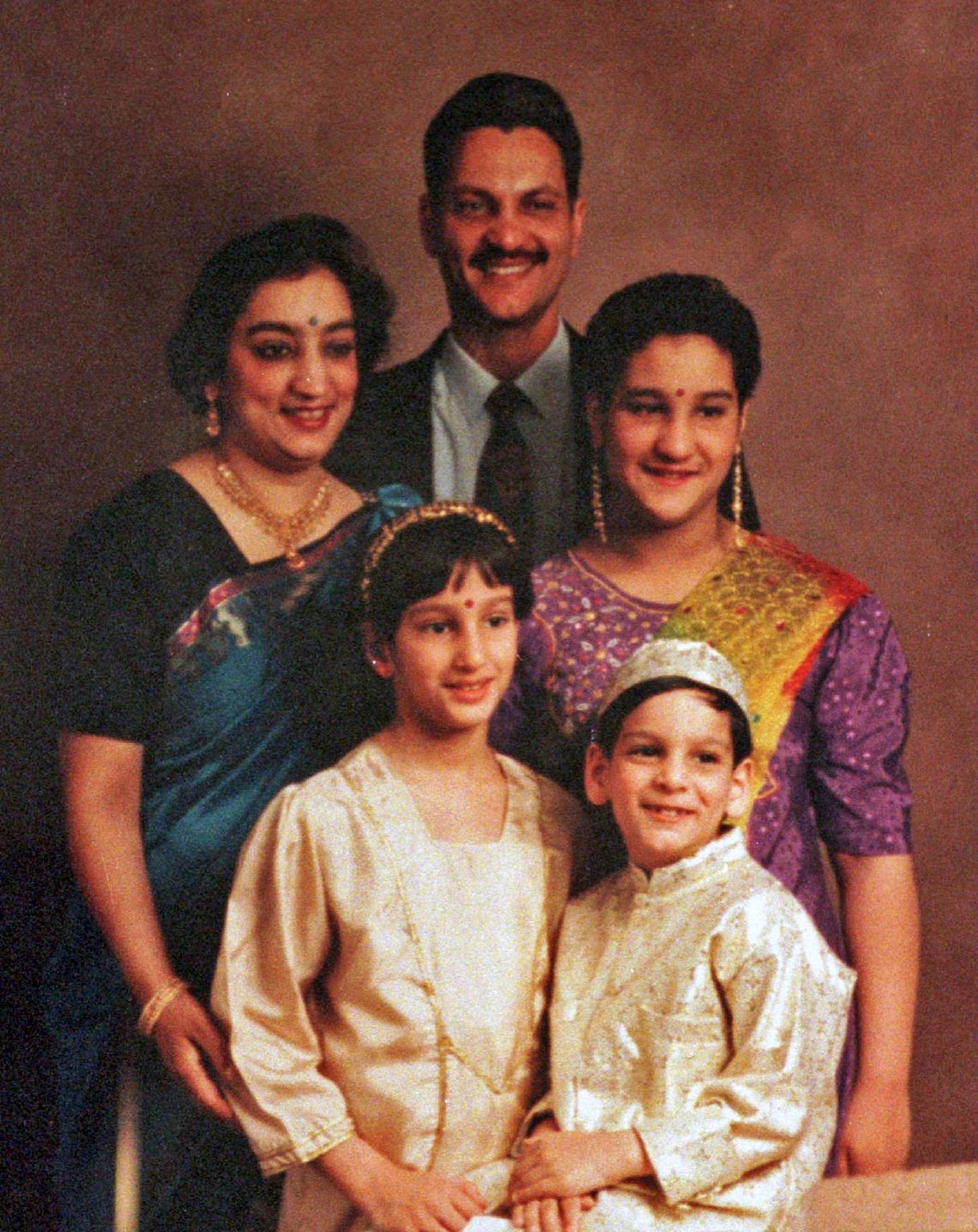

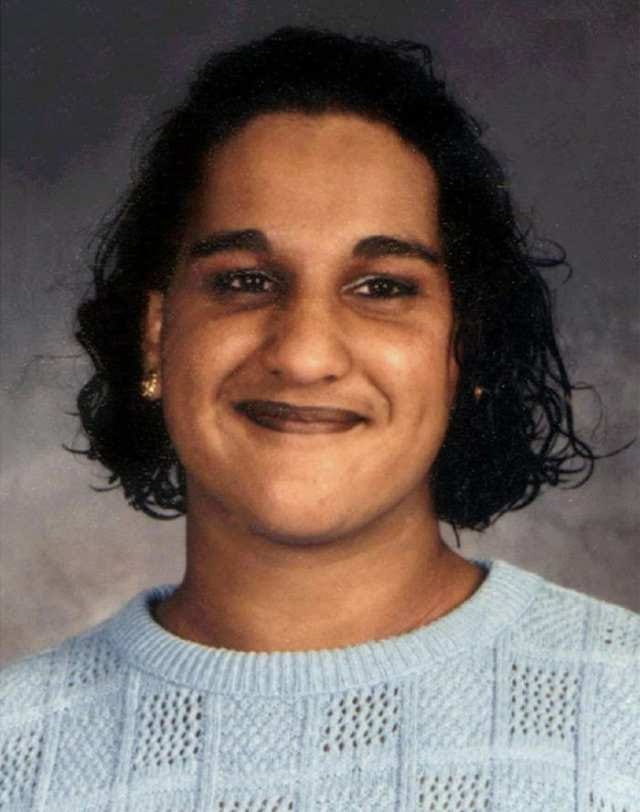

Before launching into the horror and tragedy of Reena Virk’s murder, it is important to dissect who she was. Reena was the daughter of an Indian immigrant father and an Indo-Canadian mother, raised in the tradition of Jehovah’s Witnesses. The details of Reena’s personality are fuzzy, covered as they have been by journalists and writers intent on defining her as an outcast. Most descriptions of Reena hit on the fact that she was tall, a girl of 5’8, and weighed around 200 pounds. The other, more complicated details of Reena’s existence that might have contributed to her exclusion from her peers, such as her race, her culture, her strict, religious upbringing, are glossed over in favor of an easier story. Reena was big for a girl, and on that basis alone was bullied and ostracized, and eventually killed, by other girls. The explanations of Reena’s murder all simplistically hinge on her being a girl who didn’t fit in based on her looks—as opposed to being a second-generation immigrant, a person of color who was navigating her relationship to her family and culture in the conservative environment of suburbia. Even if one were to entertain the argument that looks alone made Virk an outcast, it is important to further investigate the Eurocentric and sexist beauty standards that underpin who is beautiful and who is not. Virk, with her “big” frame and “dark” skin, did not fit into the Western standards of beauty, which have always hinged on whiteness. The media coverage of Reena’s life often mentions her “insecurity” about her weight, her height, and even her excess of body hair, as if it were an abnormality for a BIPOC teenager to be self-conscious about their appearance in a culture that perpetuates white ideals of beauty. Yasmin Jiwani, in her journal article “Erasing Race: The Story of Reena Virk”, states that, “the validity of normative standards of appearance were significantly absent in all accounts” of Reena Virk’s story. Meaning that we are given a surface level explanation for Reena’s outcast status (looks), without ever asking why she was bullied for her looks, and without acknowledgement that her “looks” inevitably also include her racial features. In short, by skirting this conversation, the media creates a narrative in which race is absent from the story.

There are also lesser-known accounts of Reena, ones that did not make the headlines. According to her uncle, Raj Pallan, Reena was happy and outgoing as a child, and was drawn to working with little children, even taking a babysitting course in 7th grade. If she had lived past that day in November, her relatives imagined her becoming a nurse, since she had liked volunteering at a local hospital. Hearing from her relatives, one can begin to imagine a different picture of a girl who, while out of place in a small suburb of British Columbia, was not doomed to be an outcast forever.