Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labour of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to check out our SHOP and our Podcast.

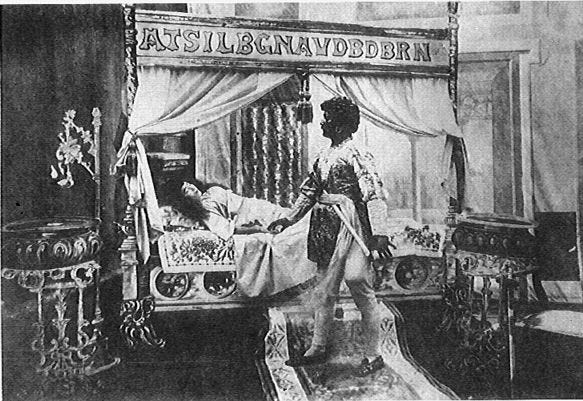

Shakespeare in India: On Stage and on Page

Shakespeare, like Hamlet’s father, haunts the postcolonial consciousness. A prominent part of English textbooks, college theatre societies, and other aspects of urban, elite, Indian life, Shakespeare continues to symbolize knowledge, education, class. The language of the colonizer lingers on as the language of social and economic mobility. Navigating the myriad contested existences of English in India is perhaps impossible, but nonetheless, this article shall attempt to uncover the first endeavours to place Shakespeare in an Indian context. This shall be approached from the perspective of the colonizer, who saw the Bard as an instrument of control and Christianity as well as the colonized, who made Shakespeare their own.

English literature, as a subject of academic study, first flourished in the colonies. This is no surprise, given that literature is commonly associated with functions such as character-building or providing a moral ideal for the unenlightened. In the colonial context, it is believed that the spread of education in English took on a more insidious role of extending social and political control over the colonized. Therefore, the spread of English in the Indian subcontinent was not a mere corollary of the change in political administration but an integral and intentional part of its proliferation.

It is important to remember, however, that every step in the colonial education policy was a subject of much debate within the colonial framework itself, not least between Orientalists and Anglicists. The former bore the belief that British administrators must assimilate themselves into the ‘native’ milieu in order to govern effectively and accordingly, promoted the study of Indian languages and literature, even in native education. Anglicists, on the other hand, used the information collected by the Orientalists in their project of ‘knowing’ the colonized to argue for a shift to Western languages and modes of thought in education.