Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labor of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to check out our SHOP and our Podcast.

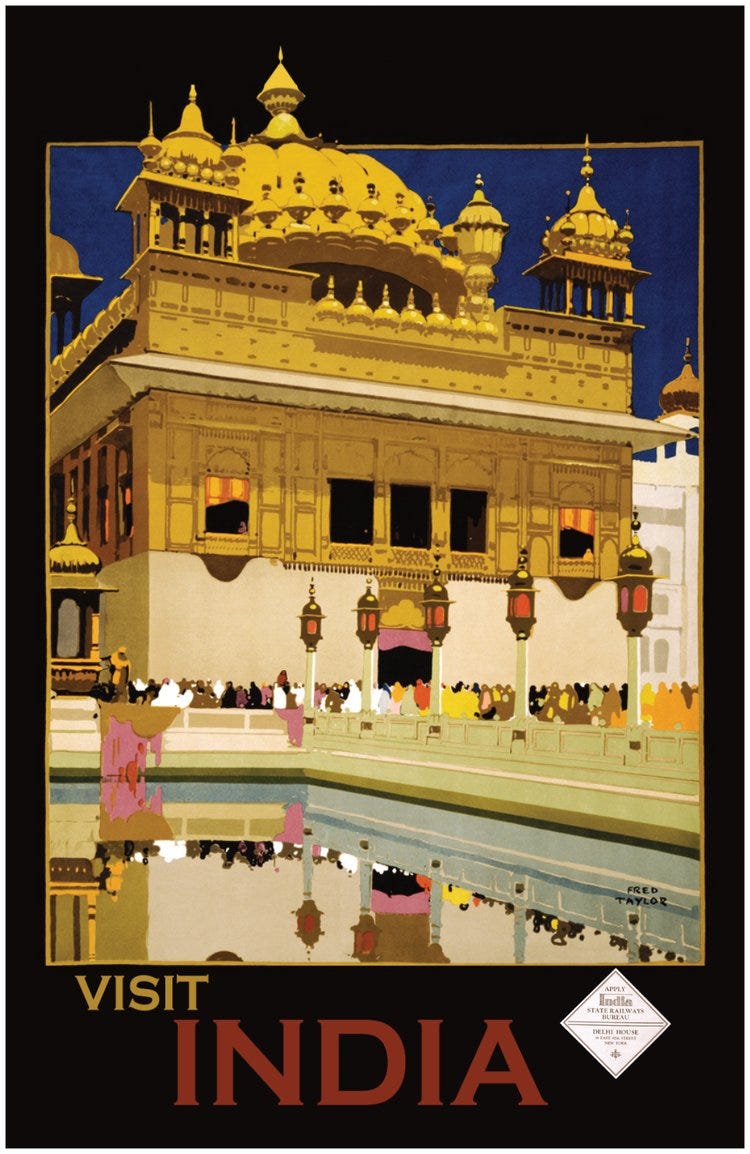

The Forgotten Wild West of Punjab

The latest Pakistani drama “Khaie” has again magnified the Pakhtun stereotype (also known as Pashtuns); castle-like mansions, mountainous pastoralism, and guns. Always guns. All sorts of guns. The hot-headed Pathan and his supreme ghairat (honor, but carrying more intensive connotations) reign supreme. Worst of all, the main characters are played by Punjabis priding over their outrageously offensive ‘Pashtun’ accents. Speaking of which, the Punjabi trope, presented most prominently in films like ‘Punjab Nahi Jaon Gi’, ‘Namaste London’ and ‘Humpty Sharma ki Dulhania’, does not give much cause for optimism either: the lazy, bhangra-dancing landlord who cannot fight for his dhoti (loincloth) without first asking for an ego-stroke from his Mirasi bard. As a Punjabi, I am deeply offended by such representations and this essay is a humble offering to challenge this conception. Under the backdrop of postcolonial historiography in the form of anecdotes, it will examine, amongst other things, canal colonization, state narratives, banditry, and the Wild West of the Punjabi doabs (an area between two rivers). The term "Wild West" has been used regrettably; it is acknowledged that the term, when applied to the Orient, has problematic, essentialist connotations, but the intention is to emphasize independence from central state authority only.

Colonialism, you’ve done it again!

The state did not emerge with colonialism. States have always existed and always attempted to incorporate local communities under the banner of statehood. But with colonialism, the fundamentally modern ideas of nationalism, citizenship, and development emerged, together with the violence of inclusion and epistemology they powered. The state continually co-opts the local, the warrior, and the rebel. Think of Bretons versus the Parisians, Uyghurs versus the Hans, and Castilians versus Catalans. Many have held that language is a dialect with an army. Scholars like James Scott encourage us to think of alternative ways of being together. Many characterize the Punjab today by its bullying of increasingly annoyed neighbors, theft of others’ resources, and cultural decline that Hanif Ramay (Punjabi writer, painter and politician – briefly governor of Pakistani Punjab) saw in the loss of the Punjabi language. Across the border, it is associated with militant Khalsaism, being India’s grain basket, and, of course, Sidhu Moosewala. But before these Punjabs came into being, a wilder Punjab existed. This is not to suggest the perpetual existence of modern Punjab’s borders stretching from Attock to Rajanpur and Murree to Haryana. A contiguous Punjab with a homogenous population and a single language, albeit colored with dialects, is also a modern invention.

So, what on earth is the Punjab? Do we define it territorially? Well, not quite. For one, the archetype “Punjabi” Ranjit Singh’s Sikh empire excluded Punjabi speakers east of the Sutlej but included many others in what are today Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Afghanistan, and even Tibet. Today, the Punjab is divided into the Pakistani Punjab, the Indian Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh. If not geographically, do we then define it linguistically? That sends us down the rabbit hole that is the Saraiki Question, among other problems. Or do we define it culturally? Thanks to German philosopher, Theodor Adorno, and his negative dialectics, we are not overly concerned with defining Punjab once and for all. Adorno reversed Hegelian and Marxist epistemological models to emphasize antithesis over synthesis. In other words, he emphasized complicating our existing beliefs. Modernity has created simplistic definitions and understandings for what are inherently complex phenomena. It is less important to come up with a single alternative definition – which leads to the same problem – and more critical to problematize existing narratives. This piece challenges our simplistic understanding of what the Punjab is and exposes the complexity that lay hidden.