Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labor of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to check out our SHOP and our Podcast.

The Questions of Partition Literature

In Gulzar’s short story Raavi Par, anxiety plagues Darshan Singh in Lyallpur (modern day Faisalabad) as he contemplates the future of his family and faith in the city. Darshan Singh becomes a father to twins as the borders of the 1947 Partition are formalized. However, there is no time and space to be joyful because after Partition, there are attacks on homes belonging to the Sikh community every other day. The Sikh community gathers in the Gurdwara for protection, and even that space faces the danger of arson by the mobs roaming around without any reprehension. The religious spaces of minority groups attacked and burned by violent mobs is a running theme in literature about the 1947 Partition of India.

On August 16th, 2023, a similar spectacle faced the Christian minorities of Jaranwala, a small town in Pakistan’s side of Punjab. As a mosque’s speaker spewed allegations of blasphemy, violent mobs burned down multiple churches, and then proceeded to torch and loot the homes of the Christian community. A picture of three men climbing on the church’s roof to take down and break the cross was harrowingly reminiscent of the pictures of violent mobs on Barbari masjid’s dome as it was razed in 1992. Why is it, Raavi Par would ask, that religious spaces belonging to minority groups are still under attack by vengeful mobs 76 years after Partition?

The author of this short story, Gulzar, whose real name is Sampooran Singh Kalra, himself had to migrate to India in 1947 from Dena, Jhelum which is in modern day Pakistan. In India, he went on to become a famed lyricist, poet, and short story writer. Yet the memories of his displacement in 1947 haunt his writings. Ravi Paar was published in a short story collection in 1999, and was also included in another collection of his work titled Footprints on the Zero Line: Writings on Partition.

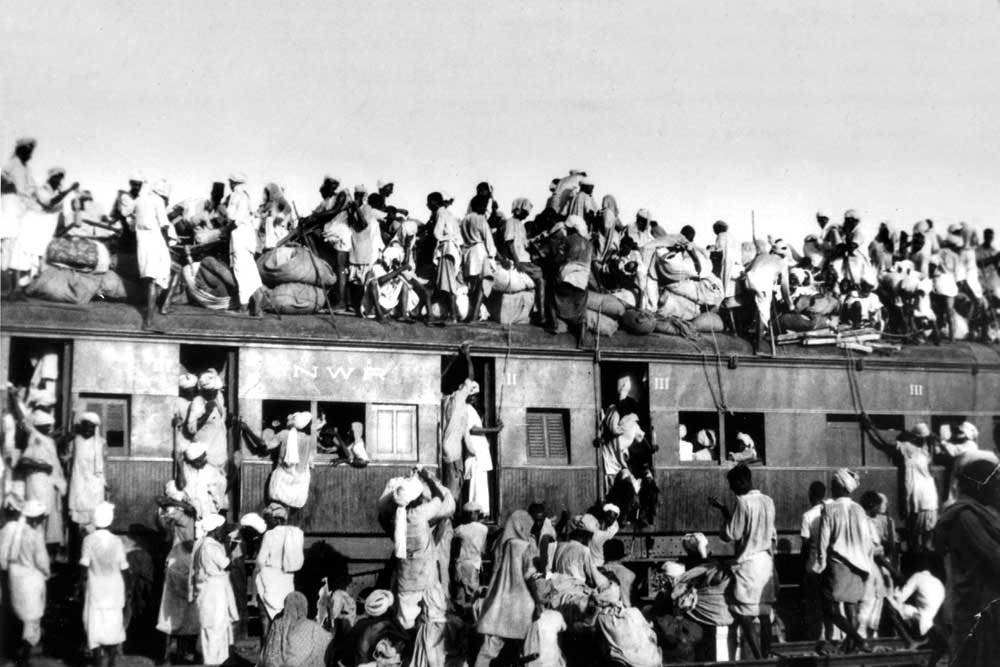

Returning to the story, Darshan Singh has to flee Lyallpur with his family. They are able to board a train which is heading to India. Tragically, one of his new born twins dies during the journey. As the train passes over the river Ravi, a fellow passenger advises Darshan to just throw the dead child in the river and do the infant’s last rites in that way. Darshan Singh takes a moment to consider, suddenly picks up his infant, and throws him out the window. In one of the most haunting endings of a Partition short story, he finds out a moment later that he had thrown the baby who was alive in the river, while the dead one still remained on the train. As he came to terms with this realization, the crowd around him shouts ‘Hindustan Zindabad’, as they saw the new borders of the newly independent country approaching.

This short story is in the curriculum of an online course that I am teaching this summer, titled ‘Partition Literature’. This was the first story we read, and many students wondered how hollow the nationalistic slogan of Hindustan Zindabad must have sounded to Darshan Singh, a father who accidentally threw his only surviving child in the river in the chaos of a forced exodus. How do you hear the word ‘Zindabad’, often translated as long live, when your two children have died in a span of hours in a train full of refugees? The glaring contrast spoke to them about the hollowness of the nationalistic slogans in the face of overwhelming tragedy.