Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labour of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to check out our SHOP and our Podcast.

The Unsung Relationship between Agha Shahid Ali and Begum Akhtar

“The true subject of poetry is the loss of the beloved”

- Faiz Ahmed Faiz to Alun Lewis, Burma

In 1974, in the same month of her birth, Begum Akhtar, the world-renowned Ghazal serenader, passed away at the age of 60, in the arms of her friend during a mehfil in Ahmedabad. Although she was ill throughout that musical gathering and was advised to cancel the remaining set, she is said to have been determined on completing her melodious singing. The whitewashed walls of the hall bore witness to the vibrant hues of her Dadras and Thumris, resonating with the poignant colors of her final ghazal dedicated to her friend, "Ae Mohabbat Tere Anjaam Pe Rona Aaya" (Oh love! Your outcome grieved me). As the final notes faded, she slowly fainted on her pavilion. It was said that the immediate cause of her demise stemmed from her dissatisfaction with her voice during her last performance, leading her to raise her pitch so high, it strained her already fragile body into a fatal cardiac arrest. With that, her era of timeless melodies on loneliness, pain, suppression, and yearning came to a pause, though not yet silent.

Her funeral was decided to take place at the mango orchard within her ancestral plot in the city of Lucknow.

A twenty-five-year old poet, Agha Shahid Ali was in New Delhi then, throbbing into painful grief, he was helpless upon hearing the news of the death of one of his greatest loves. For Shahid, she was the limit of his longing and the personification of a Ghazal itself. Like a captive, without consolation, driven by an insatiable need to honor his beloved, Shahid dashed to the airport, along with his friend, Kidwai, and took the first flight to the city of her burial procession. The ticket was quite expensive at around 400 rupees back then, so they had to borrow money from different people to complete their journey.

This was all narrated by his friend later, that upon arriving, her house was buzzing with mourners from all over the country. All around the fabric of her shroud were tales in random voices of how she had woven threads of solace and longing into the fabric of their lives. While the funeral took place late at night, he recalled how Shahid stayed up all night, in the desolation of her absence. And how at some point after the funeral took place, Shahid went to one of the empty bedrooms and started writing an elegy in her memory. He wrote the following opening lines, which later got published as ‘In Memory of Begum Akhtar’ and achieved lasting fame:

Your death in every paper,

boxed in the black and white

of photographs, obituaries,

the sky warm, blue, ordinary,

no hint of calamity,

no room for sobs,

even between the lines.

I wish to talk of the end of the world.

-

Do your fingers still scale the hungry

Bhairavi, or simply the muddy shroud?

Ghazal, that death-sustaining widow,

sobs in dingy archives, hooked to you.

She wears her grief, a moon-soaked white,

corners the sky into disbelief.

You've finally polished catastrophe,

the note you seasoned with decades

of Ghalib, Mir, Faiz:

I innovate on a note-less raga.

(In Memory of Begum Akhtar, Agha Shahid Ali)

Born in Faizabad (present-day Lucknow) to a tawaif (courtesan) mother in 1914, Akhtari experienced a tragic event at the age of four when she and her sister, Zohra, were fed food laced with poison by her father's family. While her sister passed away, Akhtari survived and at a tender age had all her joyous notions turned into numbness. ‘The grief-stricken voice that captivated an entire generation was a result of unspoken sorrows’. Her father disowned her mother a few years later, leaving them alone in the challenging period where the reformers actively sought to denigrate the music and dignity of tawaifs.

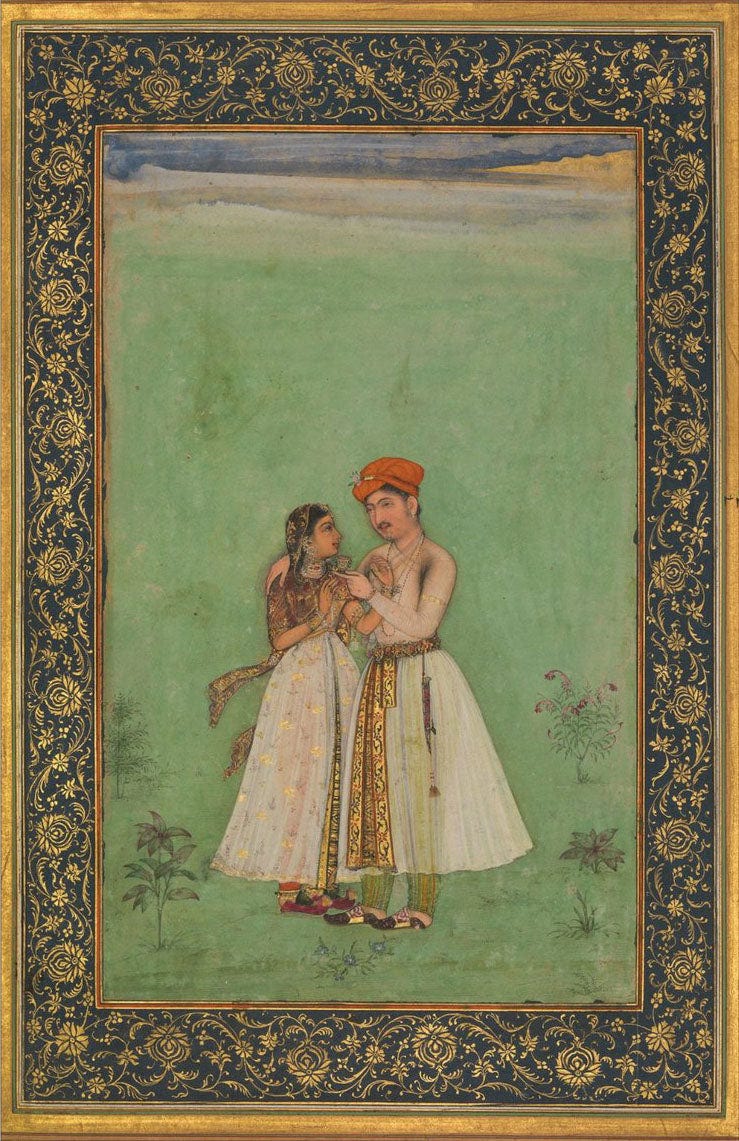

The arrival of colonial ideals, with their Victorian morality, tainted the once-revered class of courtesans. Formerly admired as embodiments of artistry and grace, they were unjustly relegated to the status of mere "Nautch Girls" meant solely for entertainment. As the 20th century progressed, the emerging middle class furthered this degradation, branding these gifted women as nothing more than sex workers. The upper-class reformers transformed the music of tawaifs into a ‘moral taboo’ dismissing their semantic content and sensual allure, which granted their thumris its evocative power.

In the accustomed tradition of her mother, Akhtari Bai was brought up and would begin performing at private mehfils, guided by classical ustads who nurtured the melodious brilliance of her craft. At the age of fifteen, she made her public debut in the city of Calcutta, alongside the legendary shehnai maestro Bismillah Khan. She mesmerized the audience with her rendition of Behzad Lakhnavi's ghazal, “Deewana banana hai toh bana hi de."