“Where is my child!?” - The Notorious Case of Javed Iqbal, Killer of 100 Children

Words by Shahzada Qasim

Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labour of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com.

Don’t forget to check out our SHOP and our Podcast.

“Where is my child!?” - The Notorious Case of Javed Iqbal, Killer of 100 Children

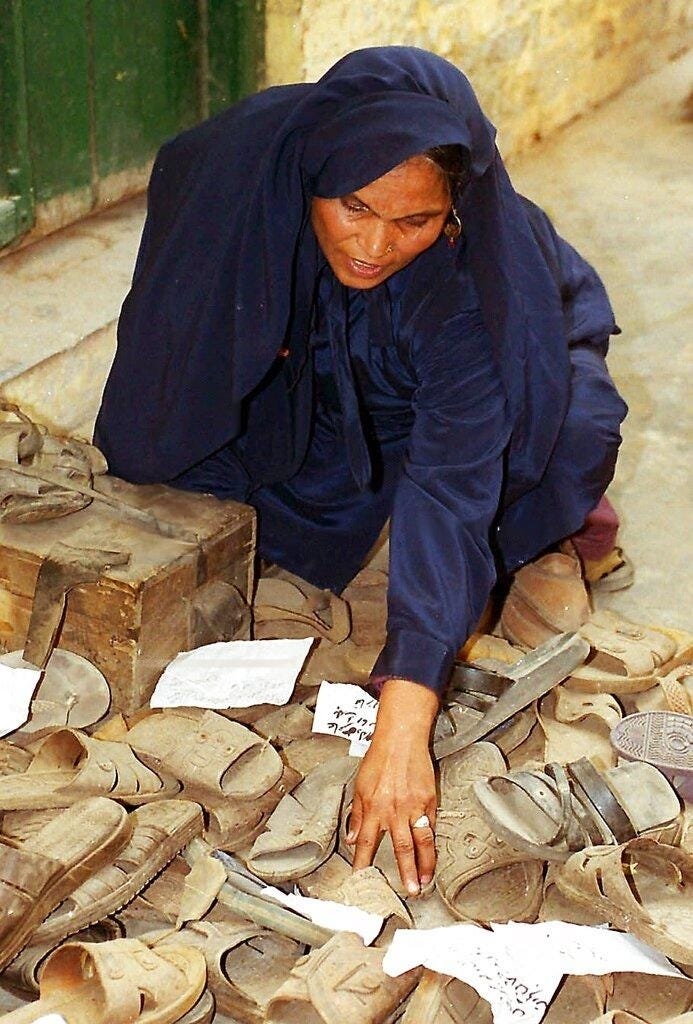

Ejaz, affectionately called Kaka by his family, and his brother were children working as masseurs in the city of Lahore. As a symbol of their religious identity – Shi'ism –they wore a steel bracelet around their ankles studded with shiny stones. One day in October, Kaka and his brother were prowling in the park of Minar-e-Pakistan, where the Pakistan resolution was passed in 1940, when another child approached them, asking: “Our boss requires a massage and he will pay you twice the amount if you come along with me?” As expected how a child laborer with endless economic burdens on his family would have reacted, Kaka rushed with him instantly. His brother accompanied him up to the house but then left for other customers. When Kaka went inside the house of the ‘boss,’ he was never seen again.

On the 20th of July, 1999, Faisal Razzaq, a 9 year old, left his home to go to a workshop where children his age spent folding cardboard into paper. At the end of the day, contrary to his routine, he did not come home. Shakeel Hassan, 13, went to the school. Returning back was not his fate. Faraz Khan went to buy groceries from a nearby store. He did not return back either. Zeeshan Nazir, 13, Abdul Majeed, 16, Tasleem Hussain, 14, and many other children today have been lost in the teeming streets or sprawling parks of Lahore, that today have been traced to Javed Iqbal. Javed Iqbal and his atrocities have become a grim chapter in Pakistan’s history.

‘Something unorthodox’

In late November 1999, Javed Iqbal penned a letter to the police station in Lahore, the provincial capital of Punjab. In the letter, he confessed to have committed the heinous crimes of assaulting and subsequently murdering more than 100 boys, all aged between 6 - 16. In addition to detailing the gruesome methods of strangulation and dismemberment that he employed, he also provided the exact location of his residence in the city, implicitly prompting, if not urging, the police to conduct a raid.