Welcome to the Brown History Newsletter. If you’re enjoying this labour of love, please do consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your contribution would help pay the writers and illustrators and support this weekly publication. If you like to submit a writing piece, please send me a pitch by email at brownhistory1947@gmail.com. Check out our Shop and our Podcast. You can also follow us on Instagram and Twitter.

Why Don’t My Friends Know My History? by Areeb Been Khan

“Why don’t my friends know my history?” To be fair, I couldn’t quite gather these words as a child, but the sentiment was there. My family moved from one DC-area suburb to another just days before my monumental 10th birthday. It was a big one. In my 10 years, my family had gone from a basement one-bedroom apartment to owning a four-bedroom single family house in a rapidly growing Virginia suburb. They began as busboys and airport newsstand cashiers and now found themselves business owners in and around the nation’s capital. Like many South Asians at the time, they were undocumented. That story, while important in its own right, is one for another day, and I often find myself teetering between pride in my anchor baby status and latent fear that discussing these matters will generate consequences as violent as the histories that are now the subject of this piece. Two decades after that near-in-distance but life changing move, I know the law just well enough to find security in my family’s immigration status. Yet, fear is often difficult to shake.

We visited our new-build, cookie-cutter suburban home on numerous occasions prior to moving in. We sent pictures back to the motherland—a place I’d not yet experienced featuring dozens of important people I’d not yet met—and planned out where everything would go. I even learned I’d have my own bedroom for the first time. More importantly, we learned that the house next door had also been purchased by a Muslim family. On one of our visits to the house weeks before moving in, some members of the family next door just happened to be visiting their new abode. I’d met two of the family’s four sons and knew instantly I had new best friends waiting for me. Shortly after both families moved in, my hopes were confirmed. The two boys, one slightly older than me and one a year younger, and I did everything together. I’d never had brothers; they had a handful. They taught me about sports, we shared food and other interests, and our sisters—one in each family—became friends as quickly as I did with the boys.

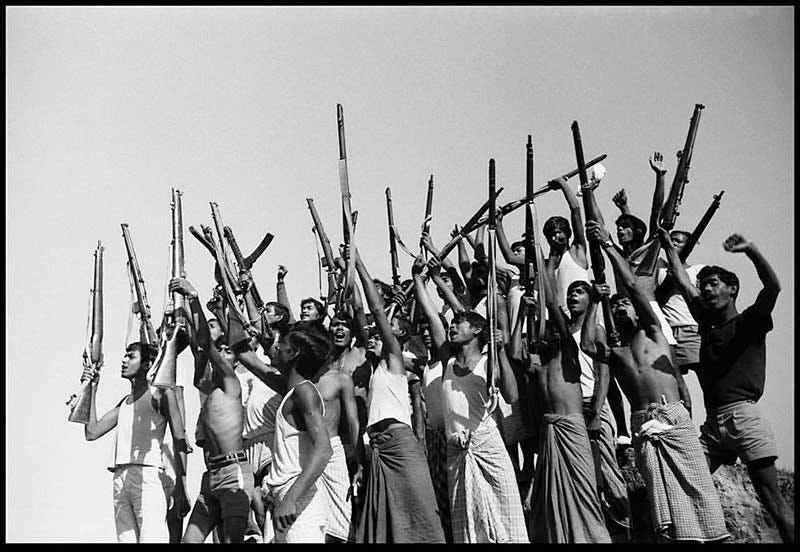

As a kid, my parents would watch Bangla television channels as a way to connect to lands to which they couldn’t yet return. In 2006, channels featured specials for the 35th anniversary of Victory Day, December 16, 1971. Having only heard about the Bangladesh Liberation War through stories fit for children and recounting my parents would do in forms they felt appropriate, I was fairly naïve in regards to the trauma they and the rest of my family had experienced. Watching actor portrayals and the sparse video footage that wouldn’t get these channels banned off of Dish Network did, though, provide me with enough context to begin learning and to eventually find my own sense of understanding, whether my parents knew it at the time or not.

One thing I wasn’t aware of until years later was the roller coaster of fear that would become my educational journey. As a kid eagerly awaiting my teenage years I suddenly became aware of what it took for me to be safe—to be a child unbothered by war and soon a young adult focused on my own growth. My parents—10 and eight when the war ramped up, respectively—began telling me stories of what life was like for them at my age. The stories were no less than disturbing, but what really frightened me was their delivery. Up to that point I’d never heard my parents speak about their childhoods in a way that made their voices tremble. As they often reminisced on the brighter points of their upbringing—swimming in rivers, time with dozens of family members, or meeting each other as working teens at the Intercontinental Hotel—I quickly realized how sheltered, for traumatic perspective’s sake, I was even compared to my older sister, who’d immigrated alongside them as a child.

Like most kids, I started talking about what I learned with my friends. It was a lonely feeling to find out that my friends simply had no idea what I was talking about. The two younger boys next door who I’d become so close with took after their two older brothers any time a foreign subject arose. Pretty quickly, it became a game to them—a vestige of a decades’ old rivalry between east and west that needed to be rehashed any time someone brought up a schism between us. It was fun for them to take jabs at me through their myopia, that so many Bangladeshis had died at the hands of their forefathers. It was clear to me that how little they cared was outweighed only by the little they knew.

I want to make an important note before I continue: I do not blame these friends for being boys regurgitating what they’d heard. We were children, after all.